AI: All Idiots

The language of the algorithms of machine learning is uncompromising and vulgar. It is the language of unscrupulous statistics with the cynical goal of extracting value (information) wherever possible. The conception of AI: All Idiots appropriates this vulgar language and lays bare the degradation of human beings into statistically more or less important objects; spectacular sources of data. To referents of stereotypes that are to be statistically confirmed and forever repeated. The AI: All Idiots exhibition project represents a cross section across “artistic” and “artificial” intelligence on a sample group of Czech artists. This engenders an attentional shift from the individual artistic products to the fact that art also exists within the context of digital technologies where artificial intelligence encounters them.

Aimee Zia Hasan (b. 2002) is a painter and artist originally from England currently living in Zlín. She is currently in her final year at the applied art high school in Uherské Hradiště and is planning to continue studying painting at university. She mostly works with oil paint but also enjoys experimenting with mixed media, graphic prints, and multimedia. Her painterly style is contemporary figurative and spatial painting with classical continuity and a focus on colourful seeing. In addition to painting, she is also active as a musician, an actress in multimedia projects, and voice acting in audiovisual art. She is an active member of Cane-yo, a young international art community, and her work was presented in Artit, an art magazine published in London.

Andreas Gajdošík (b. 1992) is an artist and coder. He focuses on useful art, socially engaged project, and artivism, which often involves programming, new technologies, and interventional, provocative positions. He is interested in ethical source software, sharing, DIY culture, and experimental forms. He was a member of the former Pavel Kolmačka collective. He is the laureate of the 2019 Jindřich Chalupecký Awar

Barbora Trnková (b. 1984) is a photographer and a postgraduate student at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Brno University of Technology. Her dissertation focuses on aspects of human-inhuman communication both in the development of technology and as an accompanying phenomenon of the very process of working on a work of art in any medium. She is part of the art duo &.

http://barboratrnkova.cz/, http://metazoa.org/

Jana Bernartová (b. 1983) is a graduate of the Faculty of Art and Design at the Technical University of Liberec, where she studied in Stanislav Zippe’s Studio of Visual Communication – Digital Media between 2003 and 2007. During her studies, she also participated in exchanges at Ľubomír Stacho’s Studio of Photography and Intermedia Extensions at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava (2006–2007) and Václav Stratil’s Intermedia Studio at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Brno University of Technology (2007–2009). She successfully completed her doctoral studies at Federico Díaz Supermedia Studio at the Academy of Art, Architecture and Design in Prague (2010–2013). She lives and works in Prague and Liberec. In her work, she explores the relationships between the virtuality of digital space and its material permeations into the material world. She follows the principles and possibilities of presets and standardisation and their possible failures. Through her visually restrained intermedia works, she comments on the current state of the world (of art).

Marie Meixnerová is a critical and theoretical writer and curator, concerned primarily with Internet art. She co-curates ScreenSaverGallery, is an editor of the Experimental cinema section at the film and new media magazine 25fps, and a curator at PAF – Festival of Film Animation and Contemporary Art in Olomouc. She teaches curatorship of Internet art as part of the Theory of Interactive Media at Masaryk University in Brno. She is also an artist active under the moniker (c) merry. http://crazymerry.tumblr.com/

Matěj Smetana (b. 1980) is a visual artist and teacher. He graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Brno University of Technology and the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. He makes installations, objects, and moving images. He is a university pedagogue and teaches various art programmes.

Michal Škapa / Tron (b. 1978) is part of the strong generation of graffiti writers of the 1990s and one of the most significant artists connected to the Czech graffiti scene. Škapa is one of the artists closely tied to the legendary Trafo Gallery in Prague and also collaborates with MeetFactory, where he has maintained his personal studio for over eleven years. As an artist, he works with various media and formats, from murals, abstract acrylic writing, and airbrushed figurative compositions to site-specific installations and spatial objects. He also works as a graphic designer, established a screen printing workshop (Analog! Bros), and collaborates closely with the BiggBoss label.

Petr Racek is a Brno patriot and film cameraman. In documentary production, he focuses mainly on the issue of (non) functioning social and political systems. He is not afraid to shoot with the camera in extreme situations. His cameraman’s portfolio includes: Kibera: The Story of a Slum, We Have More, recording the course of Michal Horáček’s presidential campaign, How I Became a Partisan, or, for example, the series Queer.

ScreenSaverGallery is a group composed of artists, curators, and academics Barbora Trnková, Tomáš Javůrek, and Marie Meixnerová. Their practice consists in searching experimental approaches to the most topical technologies and presenting these to both experts and the general public.

Tomáš Javůrek (b. 1983) is a postgraduate student at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Brno University of Technology, where is also an assistant professor. Additionally, he is also an independent book publisher, while his curatorial work focuses on contemporary internet and digital art, which he also focuses on in his dissertation research. He is part of the art duo &.

www.tomasjavurek.cz, http://metazoa.org/

Vilém Duha (b. 1981) graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Brno University of Technology (2009), where he studied at the Multimedia Studio. His work has been presented at numerous solo and group exhibitions. His main focus is on animation and relief work. Currently he is also the CEO of Truthify.

Artificial intelligence is a phenomenon that is developing at breakneck speeds. More and more models are created, closer and closer to perfection; various specialisations are developed, combined, used in digital technologies across disciplines – including fine art. At this exhibition, you will not encounter a list of these models or examples of their use by contemporary artists. We realise that however interesting and attractive the products of artificial intelligence can be, they still correspond to the composition of the data set.

At this exhibition, then, we decided to start from scratch and collect our own data set (a compendium of visual data used to teach the AI), create our own AI, and cast several Czech artists in the production role (often the domain of machines). The aim is to introduce the spectator to artificial intelligence clearly, comprehensively, and experientially, through its own methods.

The exhibition asks fundamental questions: What is the role of art in the space defined by contemporary digital technology and artificial intelligence? What is the relationship between artificial intelligence and “artistic intelligence” – the intelligence that is stored and developed as part of artistic practices? What is the relationship between art and artificial intelligence? Is artificial intelligence creative? Can art be created through a mechanic repetition of stereotypes?

And does artificial intelligence have a sense of humour?

The Data Set and Collaborating Artists

The starting point for the exhibition is what’s known as the dataset, an enormous database of image material through which Czech artists and art groups present themselves on the internet through their own publicly available websites or blogs (semi-private or private platforms on social media are outside our scope of interest) and are introduced to the public through Artlist – the largest Czech online database of contemporary artists. These portfolios provided our curious AI with over half a million digital images. Is that enough for artificial intelligence to have an idea about Czech contemporary art and be able to emulate its production?

Drawing on the data set is the trained AI programme, All Idiots, but also invited artist mediators: Andreas Gajdošík, Vilém Duha, Matěj Smetana, Jana Bernartová, Barbora Trnková, and Tomáš Javůrek. At MeetFactory, they manifest the pieces based on the data set and the output of the artificial intelligence processing the data set. There are no artists at this exhibition – the exhibition creators are in the service of artificial intelligence. The roles of humans and machines are reversed. The artistic outputs are the result of collective authorship; collaboration. Artistic and artificial products go hand in hand.

We created a team composed of several artists connected by an interest in reflecting on contemporary technologies, who were then joined by the MeetFactory team, the exhibition architect, and the programming team. Everyone had the opportunity to contribute their own input to the preparation phases. The result therefore represents the output of a collective collaboration.

We are interested in how the materials the artists use are inscribed in their works. Generally, one can say that the resultant work belongs both to the artist and to the material (in the broader sense of the world) they use. The aim was to give artificial intelligence preference, in quotation marks – to capture the creativity of artificial intelligence in the individual steps. We had to try – to a certain extent, at least – to remove human expectations. The result shows the limits of our capacity to avoid these expectations.

During the preparatory phases, we, as the artists, attempted to take a step back and grasp the internal processes of artificial intelligence, part by part. Artificial intelligence, for instance, has a particular way of comparing and then arranging images. The videos by Matěj Smetana and Jana Bernartová were created in a similar manner, organising the data set, though they were both aiming for different artistic effects.

Neural networks used at the AI: All Idiots exhibition:

1. We used StyleGAN2 by Nvidia and trained our AI on our own data set from the very beginning.

2. In order to generate jokes (on the basis of names from the data set and gender), we used GPT-2 by openai. This was a process of completing the training with text input created by us.

3. We used MobileNet V2 by TensorFlow Hub and a Spotify/annoy library to search for similarities between images. This involved the use of an already trained network. https://github.com/eisbilen/ImageSimilarityDetection

4. For editing (enlargement and denoising) the generated images, we used ISR (Image Super Resolution) models, specifically RDN and RRDN. Again, in this case we merely used pre-trained models.

The AI must first process an enormous number of images from the data set. The speed at which this takes place is much faster than humanly possible. It learns in a matter of weeks or months, but this is a computational task that would take a human being several lifetimes.

The difference between human and artificial perception and processing – the difference between fast and durational perception and processing – this is the emphasis of Jana Bernartová’s film and installation. She transferred the data set into a film whose episodes have a running time of over a hundred hours. Humans can go eight to eleven days without sleep, after which staying up longer is life threatening. In order to maintain the visitors’ wakefulness, a special environment is created to complement the video installation, containing elements that stimulate the human senses.

Sequencing 136 458 images according to one clue has taken the artificial intelligence approximately fourteen days. There are four sequences in the installation: created by visual similarity, color, composition and surface and lines. Matěj Smetana has placed the simple animations on top of four robot vacuums, and let them cruise the Meet Factory. The vacuum cleaners represent the seemingly utilitarian development of artificial intelligence development and of technology in general. When installed in the gallery, the vacuums steal away the job of cleaning workers, as artificial intelligence is expected to do in a number of professions. But these robots are just relatively stupid automatons. This is not the first time robot vacuums have been used in a gallery installation. In relation to this topic it can even be considered an ironic installation cliché.

The artistic creations result from collective authorship and cooperation. Artificial and artistic outputs go hand in hand. One image has been randomly chosen from the collected dataset – a digital reproduction of a painting, which was later loaned for the exhibition to stand as a representative of the whole database collection. A thumbnail image selected by the algorithm.

The chart on the wall is based on the original, complete data set of the Czech art scene created for the AI: All Idiots project.

Who are the heroes? Who are the outsiders? Who is the best Czech artist?

Only once you understand the data can you begin the teaching process. Do the images collected from artists’ websites provide a sufficient reflection of Czech art? The training of artificial intelligence is determined by many human decisions. The data collection itself is preceded by many human choices: the kind of data collected must be determined in advance. Many mistakes and discoveries can happen here. The vulgar language of numbers and comparison, hard incisions in soft matter.

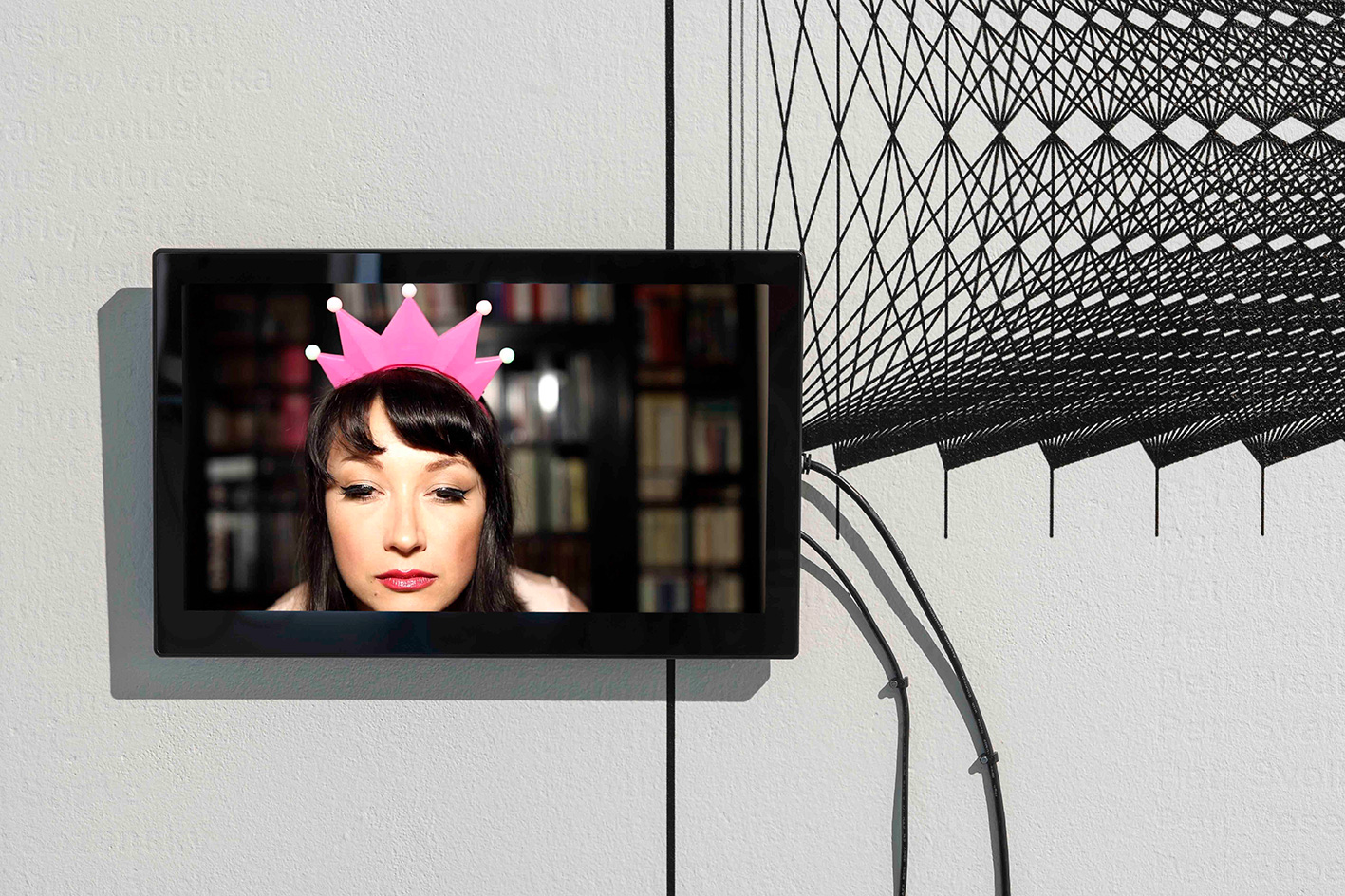

Artists – understandably – aim for the presentation of their art on the internet to look enticing, so it often corresponds to current conceptions of attractive online presentation. Barbora Trnková’s video is another form of the presentation of the data set. Using the language of YouTube vlogs, she writes down – and shows the camera with a smile – the names of the represented artists. She thus imitates the work of the “boxing ring girl” in the internet environment. Analyses of data files are another space that demonstrates both the traditional and new forms of social reproduction.

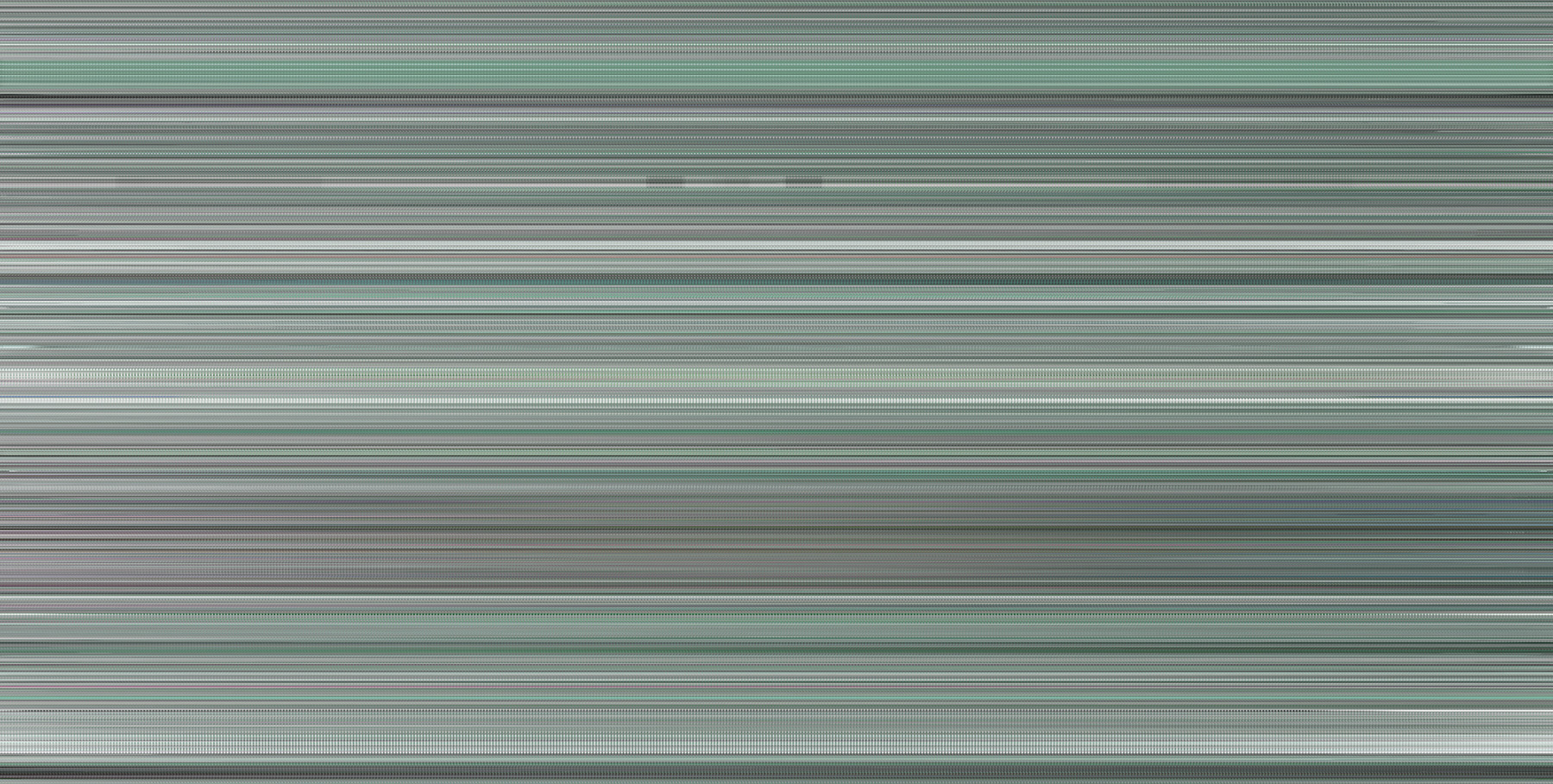

So that AI can read the images and learn to recognise them, it first has to split them into a line with the individual pixels arranged next to one another. These lines are then compared. If every image in our data set were to be arranged on a single line one pixel tall, and if we also wanted to use this method to rearrange the data set, print it, and exhibit it in the gallery, we would have a colour print 262 144 x 136 458 pixels in size, i.e. 53,33 GB. It is impossible to print such an enormous image with currently available technology, however – it cannot even be shown on a standard computer. All we can do to help you imagine it is to approximate its visual structure with a preview that is a hundred times smaller.

Andreas Gajdošík and Vilém Duha uploaded the works contained in the data set to Google Open Images, a crowdsourced data set, so they could tag them as art. Before then, this tag was connected only to a negligible number of items.

The aim of the project was to support Czech art by improving its position in the field of artificial intelligence. Specifically, the artists aimed to upload a large part of the all idiots [IM9] data set through the Google Crowdsource app to Google’s image data set. The hypothesis and conceptual aim is create a prevalence of Czech art in the “art” category/tag of an important data set, creating a power position that could potentially manifest in the future – the artificial intelligences of the future will understand “art” based on examples from Czech art, i.e. the category of art, from the AI’s perspective, could potentially merge with the category of Czech art. This is a theoretically viable situation, but the value of this act lies more in the speculative and conceptual level of this intervention.

The jokes at the All Idiots exhibition confront artists’ frequently self-deprecating sense of humour, humour as an artistic strategy, and the issue of artificial intelligence having a sense of humour of its own. Although we cannot say that AI has a sense of humour, jokes created with the use of AI are often humorous. Jokes are a highly specific form of human expression; they are based on building an expectation and then disrupting it. For artificial intelligence, this moment of disruption is extremely difficult to grasp.

Furthermore, jokes, just like AI, have the property of confirming and reproducing stereotypes. By laughing at the jokes, however, we release tension that could, in other situations, lead to self-reflection. The effect of the sudden transformation of tense expectation into nothing is shared by both jokes and the output of artificial intelligence. The jokes read by Vladimír Havlík were created by artificial intelligence using the names of Czech visual artists.

The data set is introduced here through a recording of the process of the training of the neural network – the “All Idiots” AI. During the course of this process, the neural net gradually scanned the entire data set. The speed of display was ~0.025s [approximately twenty five thousandths of a second, virtually undetectable by the human eye. In order to read it, the AI divides the image into a single line.

On the basis of this teaching process, the artificial intelligence then generated new image material – it attempted to create new Czech visual art. Of course, it is always true that the larger and more precise the original data set, the more precise the AI’s output.

In comparison: the data set of faces for This person does not exist contains seventy thousand images, so the newly generated faces can only be distinguished from human faces with some difficulty. If provided with a billion photographs of rocks, artificial intelligence will probably create a digital image that will seem like a convincing photograph of a real rock, while with a hundred rock photos, the result will not be as precise.

The question is this: does the contemporary art scene sufficiently present itself on the internet? And is Czech art similar enough to each other that artificial intelligence can mimic it? Using the application, gallery visitors could communicate with our artificial intelligence and generate their own, new, original Czech art.

Visitors could use the application to communicate with our AI and generate their own original Czech art.

The visually striking products of AI then became an inverted subject-matter or inspiration for the work of Czech painters. Who is the author of the resultant artwork? Is it even a work of art? How different is it from the work of Chinese wage workers, of those painters–labourers who copy photographs into paintings for the Western world?

Michala Škapa’s Graffiti was conceived as a response to one of the AI’s visual outputs. During the course of the exhibition, we also noticed other spontaneous reactions, such as one of the artists in the dataset including the exhibition as a group show in his portfolio, someone else using the generated image as cover art for a new single, etc.

Conclusion

Data collection and analysis incorporating AI is changing the environment of our everyday lived reality at breakneck speeds, including art and the art world. If, in the case of the art world, we work primarily from the uninformed lived experience of these changes, our output will more likely take the form of images reflecting the aesthetic typical of the output of artificial intelligence. But if we go deeper into the nature of this technology, we will discover that the core of their real aesthetic lies in the structure and processes related to the mechanisation of stereotypes.

Is AI creative? Can art be created through a mechanical confirmation of stereotypes? The creative potential of artificial intelligence consists in learning to recognise schemas and patterns. In addition to the ones we expect when arranging the data set (a collection of visual data that the AI learns from), however, it also learns those whose existence we did not even suspect. As on the surface of photosensitive material, our blind spots are gradually revealed; our tendencies, prejudices, and automatisms. If we define art as that which shows us the unseen, then artificial intelligence is an effective artistic tool.

Podcast: Barbora Trnková & Tomáš Javůrek: On Artificial (Or Artistic?) Intelligence

How does artificial intelligence learn to make art? Why is AI often politically incorrect, vulgar, and unethical? And what role does art play in today’s world, so determined by technologies? Listen to the new episode of the Tovární hlášení (Factory Announcement) podcast with two out of the three members of the ScreenSaverGallery collective, Barbora Trnková and Tomáš Javůrek, both of whom – along with Marie Meixnerová – are responsible for the AI: All Idiots exhibition at MeetFactory Gallery. We discuss not only how AI permeates our lives, but also about the capacity of artificial intelligence to create art and how and why you can teach your computer to pray.