Eva Koťátková: Interviews with the Monster

Eva Koťátková’s exhibition project Interviews with the Monster takes the form of the de- and re- construction of situations in which the majority’s encounters with otherness reveal social prejudices and the mechanisms of exclusion.

Three monumental and content-connected installations showed a spectrum of perspectives on the issue of normativity and the associated discrimination and fear of otherness, but also offered space for strengthening the empathy and emancipatory potential of the imagination.

In a quarrel or debate, have you ever used an argument such as “but normal people (unlike you) do it thus and thus”? Despite the fact that it is virtually a logical fallacy, most of us occasionally turn to this rhetorical maneuver. But what does this statement really express? Primarily, it expresses what the speaker considers “normal” or, more precisely, desirable. Even if such a statement were based on knowledge of specific statistics or facts (which is most likely not the case in most spontaneous interpersonal disputes), the use of the word normal is still notable. We could use another word instead – “most people do it this way”. The word “normal”, however, has a strange power – it is, by nature of its very essence, always judging, normative. When we tell our partner, child, or colleague something along the lines of “please, a normal person would behave in such and such a way”, we are expressing not only what we believe the purported majority would do but also what we imagine the person in question should do. By contrast, when we comfort another person by saying “don’t worry, that’s normal”, we are generally attempting to provide legitimacy to an action or reaction we paradoxically suspect an observer with no knowledge of the situation might consider inappropriate or exaggerated. The very term “normality” is thus essentially relative and contextual whilst also making a claim to universal validity in its use. And that’s what makes it dangerous.

Normality vs. Otherness

In household discussions on whether beds should be made one way or the other, how a suitcase should be packed, and so on, the use of the normality argument is usually more or less harmless. But if we transfer it to the pan-societal level, its apparent “logic” can often have extensive and profound impacts on the lives of specific people. As Filip Herza describes in his book Imaginace jinakosti (The Imagination of Otherness), the idea of “normality”, which arises from the discourses of medicine and statistics, became a cultural authority and ideal (or, in the darker cases, an outright ideology) one should aim to achieve or at least approach.1Filip Herza: Imaginace jinakosti: Pražské přehlídky lidských kuriozit v 19. a 20. století [The Imagination of Otherness: Prague’s Freak Show Culture in the 19th and 20th Centuries], Scriptorium, 2020. The establishment of “universally shared” criteria of normality thus inevitably becomes a social and political tool that contributes to discipline, control, the sustaining of the status quo, and productivity. In his book, Herza focuses on how our ideas of normality can be established and strengthened by an exoticisation of otherness. This exoticisation is founded on a human fascination with curiosities and “monstrosities”, which – to this day – become the subject of entertainment and “education”, their ultimate aim being to cement the category of normality. The second strategy through which the normative and oppressive effect of normality is applied to society is the tabooisation and stigmatisation of the “abnormal”. Fear, rejection, and displacement are all responses to otherness which Eva Koťátková considers through her exhibition Interviews with a Monster.

Koťáková’s oeuvre betrays a long-standing interest2Out of the projects known to Czech audiences, we can mention the exhibition/theatre project Dvouhlavý životopisec a muzeum představ / Justiční vražda Jakoba Mohra [The Two-Headed Biographer and the Museum of Ideas / The Judicial Murder of Jakub Mohr], which Koťátková presented in 2015 at the Prádelna (Laundry Room) cultural space at the Bohnice Psychiatric Hospital, or last year’s exhibition Otevření ryby (hodiny akvakultury) [The Opening of the Fish (Aquaculture Lessons)] at the OFF/Format Gallery in Brno. in notions of normality and the institutional frameworks that serve to co-constitute and legitimise it. She is interested in the related mechanism of (re-)education and schooling, as well as the forms and causes of social exclusion. In Interviews with the Monster, a project created in close curatorial and production cooperation directly for the MeetFactory gallery and preceded by a period of almost two years which the artist spent researching the topic and gathering material, Koťátková focused specifically on the otherness of bodily, sensory, neurological and mental “disability”.

The idea of a “disability” or “impairment” is based directly on the concept of normality. In the words of the curators of the 2013 exhibition Disabled by Normality (one of whom was Kateřina Kolářová, an academic in the field of disability studies working at the Department of Gender Studies at the Charles University Faculty of Humanities, who also took part in producing the accompanying material for Interviews with the Monster):

“The term ‘disabled’ carries with it a certain already established, codified, and institutionalised notion of what is ‘normal’. This notion leads us to differentiation based on otherness, resulting in the creation of minorities and their eventual discrimination or social exclusion.”3https://www.dox.cz/program/postizeni-normalitou In the anthology Jinakost-Postižení-Kritika: Společenské konstrukty nezpůsobilosti a hendikepu (Otherness-Disability-Critique: Social Constructs of Disability and Handicap), Kolářová also clarifies a possible socially critical interpretation of the term “disability”, a term with which many people prefer identifying over the Czech term of English origin (now somewhat neutralised in the language), “hendikepovaný” (“handicapped”): “Here, the term ‘disability’ does not refer, as it usually does, to otherness of body or mind but to the social mechanisms of exclusion and stigmatisation, disabling the people whose physique and intellect do not correspond to the supposedly universally valid and apparently natural parameters of normality.” Kolářová adds: “‘(Dis)ability’ and ‘handicap’ are not merely factual descriptions of bodily, sensory, intellectual, and psychological dispositions and characteristics – they represent an abstract and analytical category describing and uncovering forms of social differentiation and hierarchisation.”4Kateřina Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení [Disability Studies: A Different Perspective on Disability], in: Jinakost – Postižení – Kritika: Společenské konstrukty nezpůsobilosti a hendikepu [Otherness – Disability – Critique: The Social Constructs of Disability and Handicap], Kateřina Kolářová (ed.), Sociologické nakladatelství, Prague, 2012, p. 11 and p. 17. We too subscribe to this socially critical view of the meaning of the word “disability” in our use of it in the context of the exhibition Interviews with the Monster. We must also bear in mind that the term “people with disabilities” is also stigmatizing, as it upholds the separation of people on the basis of difference.5In the context of the Czech language, the term “disadvantage” is perhaps somewhat more adequate, as it indicates more clearly the structural nature of the disadvantages these people have to face. As Kolářová points out, a thorough formulation should go something like “disadvantaged by notions of normality and compulsory ability”.

Talking and Silent Heads

Koťátková also disagrees with the notion of a “natural” duality of the normal and abnormal and attempts to disrupt these schemes in her work through the use of empathy and imagination. At the Interviews with the Monster exhibition, the role of a case study for thinking about these issues was filled by materials about relatively recent cases (2019) in which inhabitants of several Czech townships protested against the development of projects providing sheltered housing in their vicinity.

In the front section of the gallery, Koťátková – along with the exhibition architect Dominik Lang – created an environment reminiscent of a recently unfinished construction site of one such sheltered housing community. At the construction site, we met characters who represented real and invented (but possible) participants in the aforementioned “rows”: the mayor, the governor, the architect, the chairwoman of the petition committee, the director of the NGO providing housing for disadvantaged people, a woman supporting the inclusion of disadvantaged people in her local community, and a man who aggressively resists the construction of sheltered housing on the plot neighboring his. For the script of this audio drama, Koťátková used a collage of real statements by council members and residents taken from the media, complemented by several fictional speeches by the architect and a character referred to as The Child’s Fear.

The audio drama, which was conceived as a spatial sound installation whose mouthpieces were the individual giant textile heads, gradually doubles back on itself – the arguments repeat, so what gradually comes to the surface is the misunderstandings and the unresolved nature of the entire affair. The “construction site” itself completed – mostly through a plethora of nonsensical details – the feeling of absurdity or hopelessness. In addition to the distended heads of the speakers, we were also confronted with the limp, silent heads. These represented the potential clients of the new housing, who are essentially puppets in this affair – either as the feared “bogeymen” or as the ones “in need” who others must stand up for. However, despite the long negotiations and various media appearances, no one gave them any space to express their own opinions and needs. And so, they remained silent even here…

Where Does the Monster Sleep?

The next part of the exhibition was in low lighting, reminiscent of a cave or basement. Across the room, in the darkness, rested a tentacled monster. By itself, it was far from terrifying – quite the opposite, it offered visitors the opportunity to bury themselves into its soft tentacles and listen. Anxiety, however, sets in as we listen to its story. We learn about the stories of real people and fictional characters who speak of discrimination, bullying, and loss of legal capacity.

Their experiences concern the behavior of bureaus and institutions, the power and despotism of medical diagnoses, the issues of the job market, exclusion from groups, derision and the (im)possibility of living alone and becoming independent. One of the causes of their tribulations is other people’s – that illusory majority – fear of otherness. This is why Koťátková shifts the meaning of the word “monster” in the exhibition’s title away from the pejorative connotations associated with the traditional understanding of “monstrosity” as otherness,6An infamous example of such an understanding was the fairground freak show. introducing instead a Social Monster that feeds on society’s irrational fear of the other and the unknown; on attempts to arm itself against this other with various defense mechanisms and push it out to the margins.

Koťátková explains: “The Social Monster is an embodiment of our learned fears and worries. As inequality and oppression grow, it too grows – it is the collective body of our emotions. It tells its story at the exhibition because it cannot stop. It has its bed in the gallery, and perhaps it walks the city at night and comes back a little larger. It speaks of what it is like to be labeled the other and what forms the fear of the unknown can take. Our society is based on inequality and exclusion. Since childhood, a fear of the other, the unknown, is purposely created within us. There is no time for otherness – it represents a threat to the system. What is different is often described as dysfunctional, incomplete or sick; as something that needs to be repaired or removed. A different movement, gesture, or sound are immediately diagnosed, corrected, treated. Imagination is tolerated only as a means of dreaming, not as a tool of change. We are taught one set of stories while other sets are silenced and erased.”

Not only does Koťátková point out the open negation of otherness, which can manifest both in being actively insulted and in being passively ignored,7A different manifestation of the objectification of otherness – less clear and therefore acceptable to many people – is making the disadvantaged into heroes: “Disposing of negative epithets is not enough – even seemingly positive assessments reinforce and reproduce the stigma of alterity. Admiringly looking up to the ‘disabled’ as heroes who tirelessly overcome their fate is the other side of the coin of abjection and the certainty that we are not the ones who are ‘disabled’. Both forms of stereotyping, the negative and the positive, stigmatize and aid oppression.” – K. Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení, p. 14. she also notices the problematic nature of attempts at correcting or reducing differences. Kateřina Kolářová also frequently points out the power-based nature of medicine and the potential stigmatization of diagnoses: “Exclusion and surveillance have been replaced by ‘regimes of treatment and help’ (…) ‘The birth of the clinic’ ushered in the participation of medicine in the dream of normality and established medical discourse as one of the central discourses to have power over the content of the term ‘normality’ and, by extension, over individual bodies and minds. (…) Regimes of treatment and charitable aid could have been attempts guided by the enlightened motivation to include otherness, but paradoxically, they laid the foundation for the power structures that lead to the repeated exclusion of the ‘handicapped’, the abnormal and different – this time, however, the exclusion takes place through a cluster of rehabilitative, pedagogical, and therapeutic practices.”8Kateřina Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení, p. 23 and p. 25.

The tangle of societal constructs and prejudices that lead to or aid the fact that one group is considered as citizens enjoying full rights while others have their legal capacity taken away is a complex field explored by the discipline of disability studies, as well as many civic initiatives, activists, and artists. Koťátková herself is interested in the issue of education and the potential to support a positive perspective on mutual differences in childhood. It is no coincidence that one specific role in Koťátková’s narrative about building sheltered housing is that of The Child’s Fear – i.e. not the child itself, but the element of fear which the child acquires through observing the reactions and arguments of grown-ups. Once again, Koťátková thus draws attention to the mechanisms that lead to an adoption or passive acceptance of our positions. In real discussions on the subject of sheltered housing that took place in various Czech townships, many of the opponents proposed an especially frequent argument based on the notion that children in particular should not be exposed to people who are different in some way.

Newsroom of the Imagination

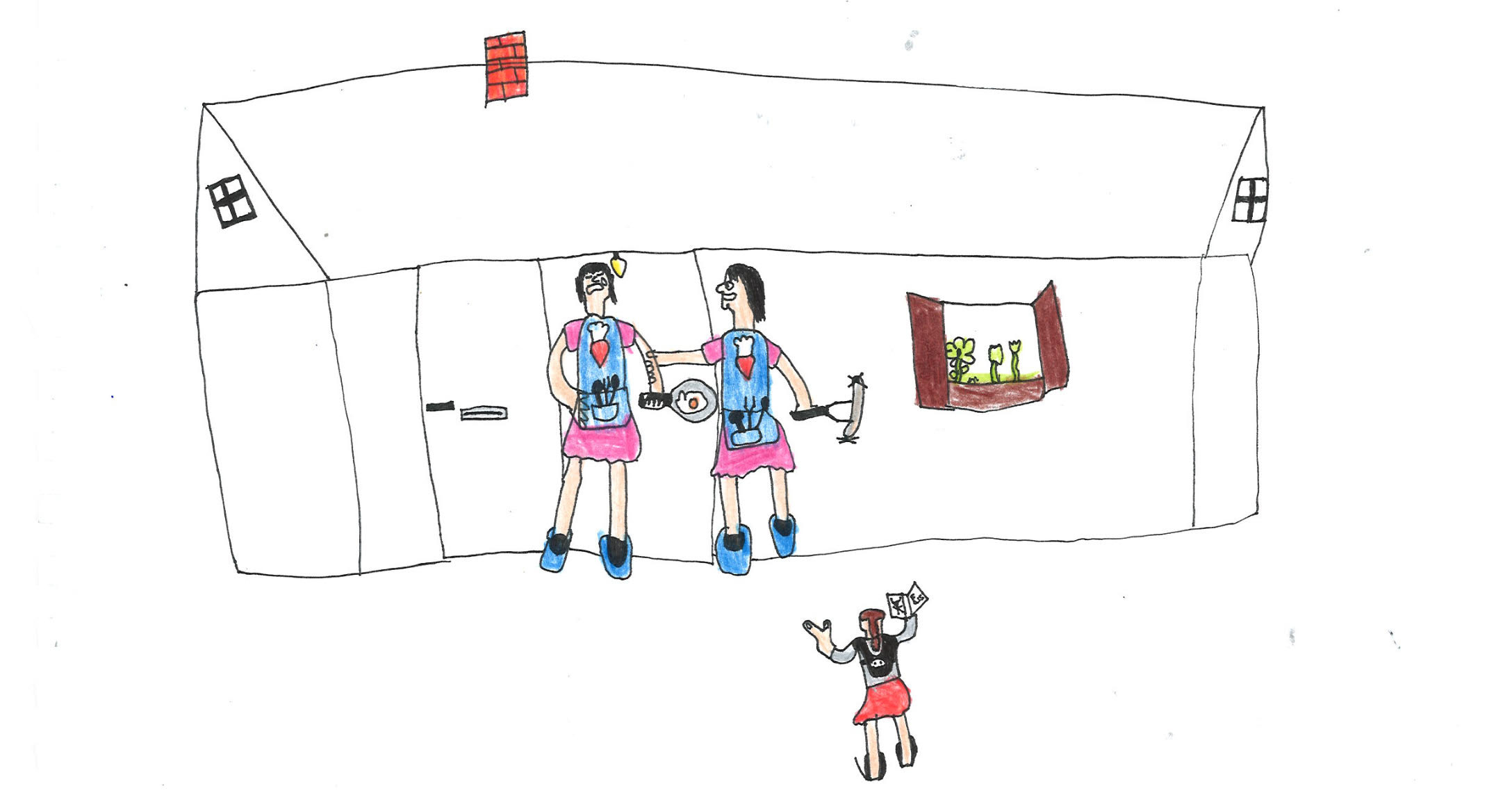

Koťátková, on the other hand, has a strong sense of the child’s “unprejudiced” nature (which we must, at the same time, avoid idealizing, as its “contamination” with social patterns takes place from a very early age) as a potentiality that is open to the radicality of imagination and empathy. This is why the third component of the exhibition was conceived as a communal space dedicated to encounters, discussions, and creation. A light room with huge fabric newspapers on the walls and a large table at its center – the height of the table is designed to accommodate children who visit the exhibition – represented the Newsroom of the Imagination. It is crucial for Koťátková’s work that, in addition to critique, positive approaches also have an irreplaceable part. The attentive listener could notice that even the monster’s narration included dream narratives – dreams of something better. Koťátková believes that imagination has an emancipatory potential, which is why the third installation was designed for children (and other groups) to communally imagine change and various visions of a better world, as well as how to practically achieve it together. The fact that this room represents a newsroom also symbolically suggests the ambition of rewriting the narrative of misunderstanding and denial set out in the audio drama from the first exhibition room. In place of the evasive, self-justifying, and outright hostile statements taken from media reports on the affair, the giant pages of Koťátková’s fabric newspapers provide a space for new narratives – narratives of understanding and acceptance. We should therefore not consider Interviews with the Monster to be an exhibition that provided a space for the silent contemplation of an already finished and self-contained “aesthetic object” composed of the individual installations, but see it instead as a space for urging the visitors to action – a space inviting us to use both our critical reasoning and our imagination, as well as to meet other people and enter into dialogue with them. The interviews with our Social Monster are meant to represent only a beginning.9We can point out here that an exhibition that is closed to the general public for months due to the pandemic is, paradoxically, itself a kind of memento of accessibility. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, what most of society considers a matter of course, such as freely visiting exhibition spaces at any time, became impossible for most of society (with the exception of professionals and reviewers). The current situation is thus a sort of reminder of the inaccessibility or low accessibility of our unprepared cultural institutions, to which groups of people with various forms of disability are commonly exposed to. The present situation can perhaps help institutions shed light on these issues and think more deeply on how to overcome them.

One element that Eva Koťátková found particularly interesting when researching discussions about “problematic” new building projects was the phrase “fear of the unknown”. It was heard repeatedly from numerous parties. Some opponents of the project appealed to the fact that it is natural to fear that which we do not know.

This aspect partly reflects insufficient communication and discussion between the various interested parties (regional government, municipality) and, particularly, from the representative bodies to the inhabitants who were set to become the neighbors of people with a “handicap”. In this respect, fear of the unknown is, to some extent, understandable, and greater transparency and better communication and education could have at least somewhat tempered the negative reactions. It is also worth emphasizing here that Interviews with the Monster was not about pillorying specific people, even though some of them clearly mismanaged the responsibilities of their position, while others did not shy away from expressing themselves in essentially hateful ways. This is part of the reason why the exhibition included no specific names of places or people. Personal responsibility is one thing (and just like the exhibition does not wish to pillory, it also certainly does not wish to make light of or excuse personal responsibility), but what seems even more significant in the long-term and broader context is to consider the pan-societal mechanisms that create and influence our responses in such situations.

When the speakers talked about the “fear of the unknown”, what they meant by this unknown were the “handicapped” clients who were to become their neighbors. That unknown, however, was also the idea of coexisting with them, living in their immediate vicinity. Such an approach, however, is at its very core a vicious cycle. If instances of human otherness represent the unknown to us and we feel anxious when confronted by this unknown, by refusing contact, we merely affirm ourselves in our fears and prejudices. But if we explore these fears with close attention, we may realize they do not stem from otherness in and of itself, in some absolute sense of the word, but rather from the fundamental impossibility of truly firmly defining the borders of such difference (as well as the borders of “normality”). It is the lack of clarity of these borders that elicits anxiety, as it is a reminder of the fragility and imperfection of us all – even those who seem to fit better with the current notions, norms, and statistics on “normality”. If we begin to admit the causes of this fear of otherness; begin to reconsider the imperative of ability, it can end up being a liberating process.

As Kateřina Kolářová puts it: “The demand for the continuous affirmation of an ‘abled’ identity forces every subject to abject bodily otherness and distance themselves from any suggestion of failure. The rejection of ‘disability’ by the ideology of ability is harmful precisely because it forces the establishment of distance instead of a recognition of similarities and mutual dependencies that necessarily tie seemingly able bodies with the corporeality and mind that is incapable, dysfunctional, ‘handicapped’. (…) The identity of the capable, abled, and fit subject must be constantly performatively reaffirmed, repeatedly and infinitely fulfilled. Even so, ability remains a goal that is impossible to fulfill and perpetually unsustainable – in the end, our physicality or rationality will fail us, the supposedly un-handicapped and abled, and not only because of human mortality, but also because the normative demands of the ideology of health and ability are, in their very essence, inaccessible and harmful.”10K. Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení, p. 22.

This is why the phrase “fear of the unknown” also contains within it one of the possible responses to the problem of exclusion: if we stop relegating otherness to the margins, to narrowly defined zones, but instead work to make it more present in society, fear of it will diminish in the way Koťátková dreams of. The social monster will stop growing and instead begin to shrink – until it ultimately remains only a tiny little monster such as we found in the Newsroom of the Imagination. Perhaps then we will start perceiving otherness more as an essential component of human nature, as something that is not a tool with which to differentiate each other, but instead as something that serves to enrich us all.

Afterword: Learning Differently, Exploring Otherness

The Interviews with the Monster exhibition was part of a long-term program series, Other Knowledge, at the MeetFactory gallery, with which it resonated on several levels. The first of these, of course, is the subject of otherness itself, as it arises from discussions about normality. As Kolářová notes, the fear that mental otherness provokes, and which are repeatedly seen in the disagreement of the individual communities with being placed an institution for the “handicapped” in their city, are “manifestations of an anxious denial of the possibility that a healthy, rational, self-sufficient, and autonomous subject – the Enlightenment idea of the individual that most of us identify with – could bear any resemblance to its supposed opposite. (…) Being healthy, abled, capable, and therefore ‘normal’ has become an unquestionable prerequisite for a person to live a fulfilling life, as well as a condition for acknowledging their civic status and humanity. (…) If modern society identifies this strongly with the idea of scientific and technological progress and the capacity for correcting the imperfections of nature, then the incurable body becomes an affront to the power of modern medicine and technology, and ‘disability’ becomes the opposite of progress and development. (…) But in fact, the ability of the subject depends on the capacity to fulfill demands placed on the ‘responsible citizen’, and on operating as effectively as possible within the system of capitalist exchange.”11K. Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení, pp. 12, 17, 23.

The Other Knowledge project focuses precisely on those areas and ways of learning, knowing, and creating worldviews that go beyond the Enlightenment – or generally rationalist – idea of epistemology, widely favored in our time and culture (European/modern), or rather, favored by the dominant social systems and hierarchies such as capitalism and the patriarchy. The principal servants of this prevailing epistemological model based on rationalism are the natural sciences. Unfortunately, this tradition of Western thinking is also linked to power structures based on oppression (colonialism, patriarchy) and extractivism, which contributes to the social, economic, and ecological problems of the present. In the exhibitions that make up the Other Knowledge series, we attempt to search for alternatives to the dominant rationalist model of knowledge. It is this creative power of the imagination and the emotionally affective effects of empathy that, as Eva Koťátková believes, provide ways of looking at the world and acting in it differently, in new ways, moving beyond categories, assessments, and diagnoses that can be enormously reductive and restrictive.

Within the environment of the gallery and the art world as such, the Interviews with the Monster exhibition refered to the knowledge and discourse of the aforementioned field known as disability studies, which is “based on the register of general humanities and social science research, offering an alternative to the dominant form of knowledge, which primarily pathologizes, medicalizes, disciplines, and individualizes physical and mental otherness, thus depriving it of its socio-cultural context. Disability studies identifies and analyzes the relationships between disability and dominance, thus contributing to social change. (…) From individual ‘otherness’, disability studies turns its attention to the social, political, and cultural interpretations of these terms and the ways in which, in today’s society, the category of (dis)ability becomes a strategically important means of organizing and controlling not only the ‘handicapped’, but all of society.”12K. Kolářová: Disability Studies: Jiný pohled na postižení, p. 15.

If we wish to learn about disability and also acquire knowledge in different ways, forming connections across various fields – such as art on one side and academic research on the other – can open up unexpected perspectives or productively complement each other. In any case, what is most necessary is to maintain a spiritual openness and internally cultivate a sensitivity to each other and to the outside world more broadly. The “other” that we wish to know – or at least strive to know – is, after all, all around us. It shapes the world we live in and it shapes us, because otherness is a creative principle of life, not an exception or deviation.

This audio play was presented in the first installation in the form of spatial sound built into the textile heads. It is a collage of statements of individual figures active in cases of public rejection of the the construction of housing for disadvantaged people. Supporters and opponents are represented, as well as representatives of the local political representation.

Text for download here

This collage of testimonies of real and fictional characters was part of an installation with the resting monster. It represents a mosaic of statements about discrimination, bullying or deprivation of self-determination.

Text for download here.

The fairy tale Red Riding Hood, Danni and the They-Goblins was created in connection with the exhibition Interviews with the Monster and it brings reflections on our relationship to others (especially to those who are somehow different) and to the environment where we live. The author of the fairy tale is the poet, publicist and theologian Magdalena Šipka, who, like Eva Koťátková, also works in the Futuropolis: School of Emancipation project team.

Text for download here.

Eva Koťátková (*1982) is a fine artist actively involved in the Czech and international contexts. She received her Master’s degree from The Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (AVU) and her Doctorate from The Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. Koťátková was the Jindřich Chalupecký Award Laureate in 2007. She is the co-founder of the platform Institute of Anxiety, which creates a space for cooperation between artists, theorists and activists. Her work explores forms of power, manipulation, discrimination and control foisted by institutions on those who defy norms (or what is considered normal) in some way or another. Using various media, Koťátková then searches for other models of functioning, communication and sharing which would enable individuals and collectives to act in more free, equal, and empathic ways. She works with marginalized stories and emotions often inviting children to collaborate with her. Koťátková has exhibited at the Istanbul Biennale (2019), The Metropolitan Museum in New York (2018), 21er Haus – Museum for Contemporary Art in Vienna (2017), Sonsbeek (2016), The New Museum Triennial in New York (2015), Schinkel Pavillon in Berlin (2014) and the Venice Biennale (2013).