Planted in the Body

Adéla Součková (*1985 in Opava, Czech Republic) is a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Dresden. In her artwork, she develops complex critical and pictorial language that ranges from drawing, performance, and installation to video performance and poetry. Her paintings, drawings, performances, and installations are permeated by a comprehensively understood poetics connected with the language of symbolic references as well as with the moment of visibility of artistic and physical gestures.

Alexandra Cihanská Machová (*1985 in Sabinov, Slovakia) works and lives in Prague where she got her Master’s degree from Center of Audiovisual Studies at FAMU. Her main means of expression are various forms from acoustic instruments, field recordings, live coding, and others, but she often connects them with other media. She works on, more intense, sound in space, sound installation, and current, sound in a virtual environment. She also does music for film, theatre, or radio, and works with moving image.

Corinne Silva (*1976 in Leeds, United Kingdom) gained her PhD from University of the Arts London in 2014 and since then she developed a lens-based practice focusing on the landscape as a relationship between its culture, geography, topology, and botany. Her works not only encompass the world of living beings, but inanimate matter as well. This art is expressed through the means of photographic installations, multi-screen moving images, textiles but also mixed media works. Her installations “Garden State” and “Wounded” deal with the regaining of the territory and establishing boundaries, borders even, by the means of planting.

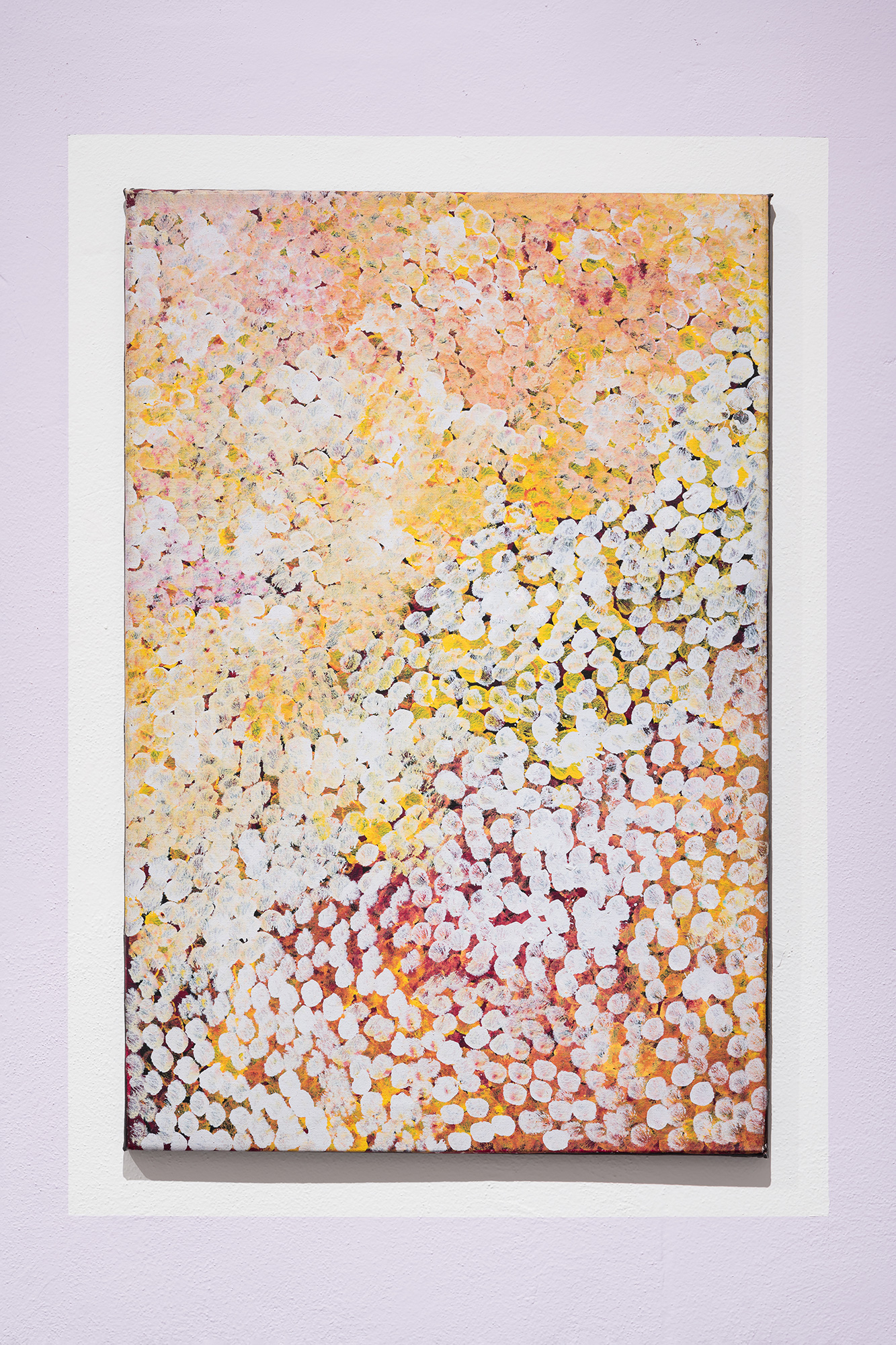

Emily Kame Kngwarreye (*1910 in Utopia Community, Australia – †1996) grew up to be an ancestral custodian and thus had been painting for decades when she was introduced to a new medium, batik, in 1977. This community project furthered her talents until she finally transitioned to acrylic in 1988 due to her deteriorating eyesight and convenience. She produced many artworks in the aforementioned medium with varying styles, ranging from intricate dots to her “dump dump” style which used a shaving brush. She often depicted the terrain and heat shimmer and later even “Yam tracks”, strange growth patterns of the Yam, vital, but difficult to find plant needed for survival in the desert. The plant was of special significance to the author, since her middle name, Kame, represents the yellow flower of the yam that grows above the ground.

Laura Huertas Millán (*1983 in Bogóta, Columbia) works and lives in Paris where she earned her PhD. Thenceforth, she has produced works in the specific genre of Ethnofiction, which is a method of compounding anthropological evidence with elements of creative storytelling. Themes of her works include imperialism, objectification of non-Western bodies, or post-colonial Others. Her works were presented in solo exhibitions, group exhibitions, and film festivals.

Luiza Prado de O. Martins (*1985 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) is an artist, writer, and researcher whose work examines themes around fertility, reproduction, coloniality, gender, and race. She holds an MA from the Hochschule für Künste Bremen and a PhD from the Berlin University of the Arts. Through performance, video, and installation, her work investigates how colonial gender difference is inscribed on bodies through technologies and practices of birth control.

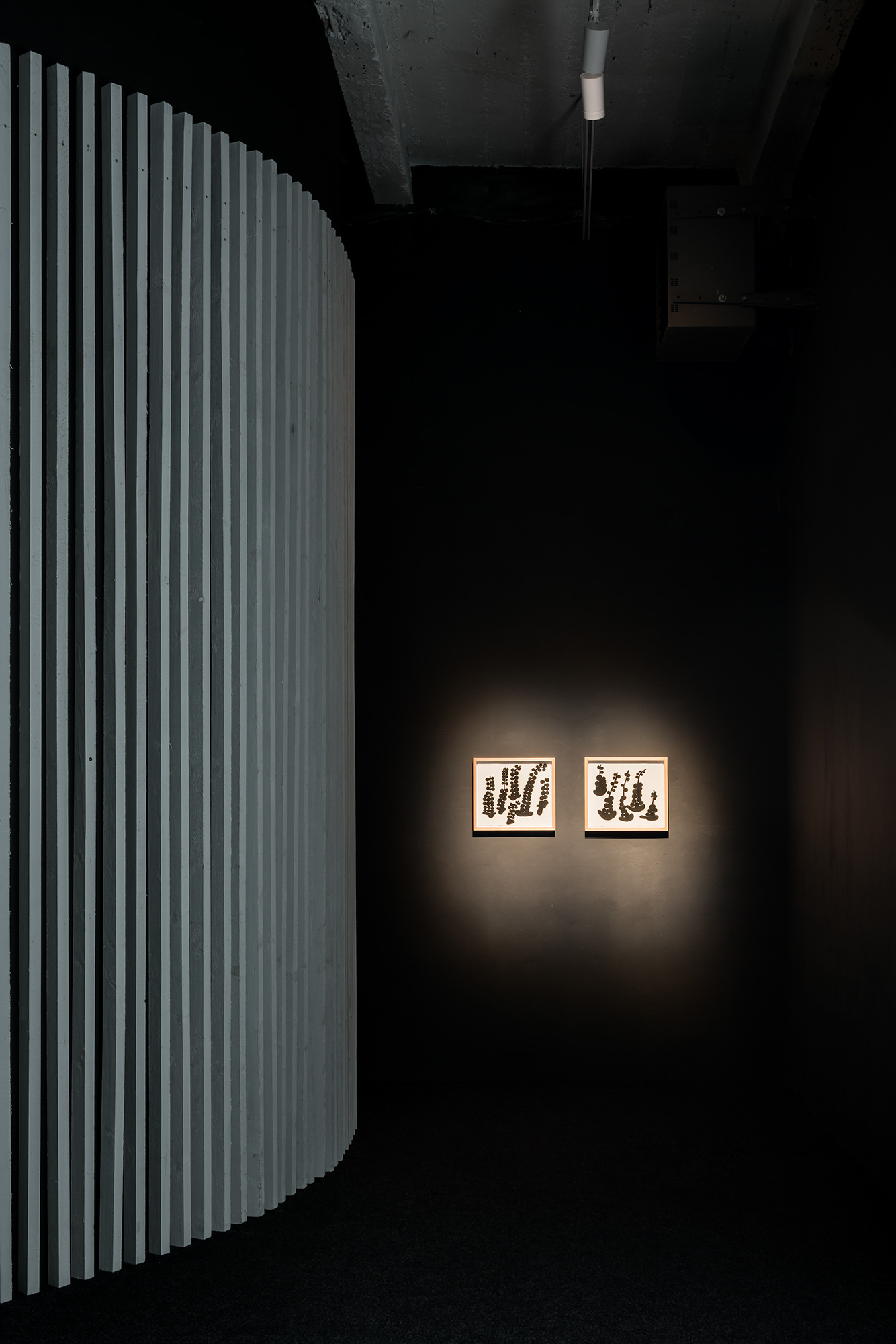

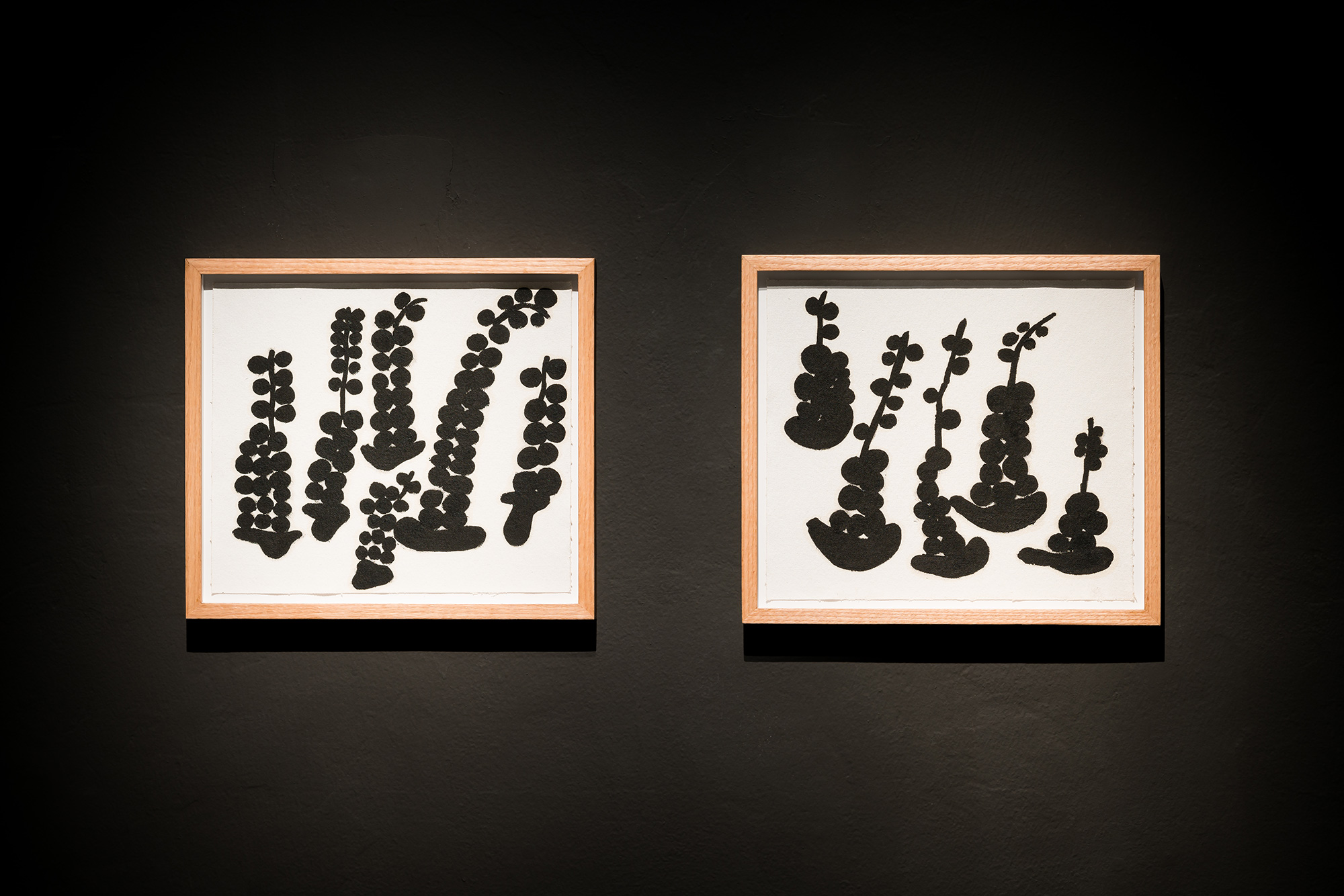

Nikola Brabcová (*1987 in Prague, Czech Republic) deals in her work with the layering of paintings and the creation of installations in which the relationships between individual paintings and objects are more important than individual artifacts. Their motifs are mostly shapes based on nature which disintegrate into abstract forms and new situations. Her latest work deals with soil and natural materials. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, exhibited at the Entrance Gallery, Jelení, MeetFactory, and at the Zlín Youth Salon 2021. She participates in the project-space Prototype and Artyčok.tv online TV.

Saodat Ismailova (*1981 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan) is a filmmaker and artist who graduated from Tashkent State Art Institute and was then granted a residency in Benettons Fabrica Research and Communication Center in Italy. This was the birthplace of her documentary Aral: Fishing in an Invisible Sea, a film about a human condition in an inhospitable environment. Then followed a residency in Berlin and in OCA Norway in Oslo, where she developed her short film The Haunted. Her most recent academic accomplishment was graduation from Le Fresnoy in Tourcoing in France.

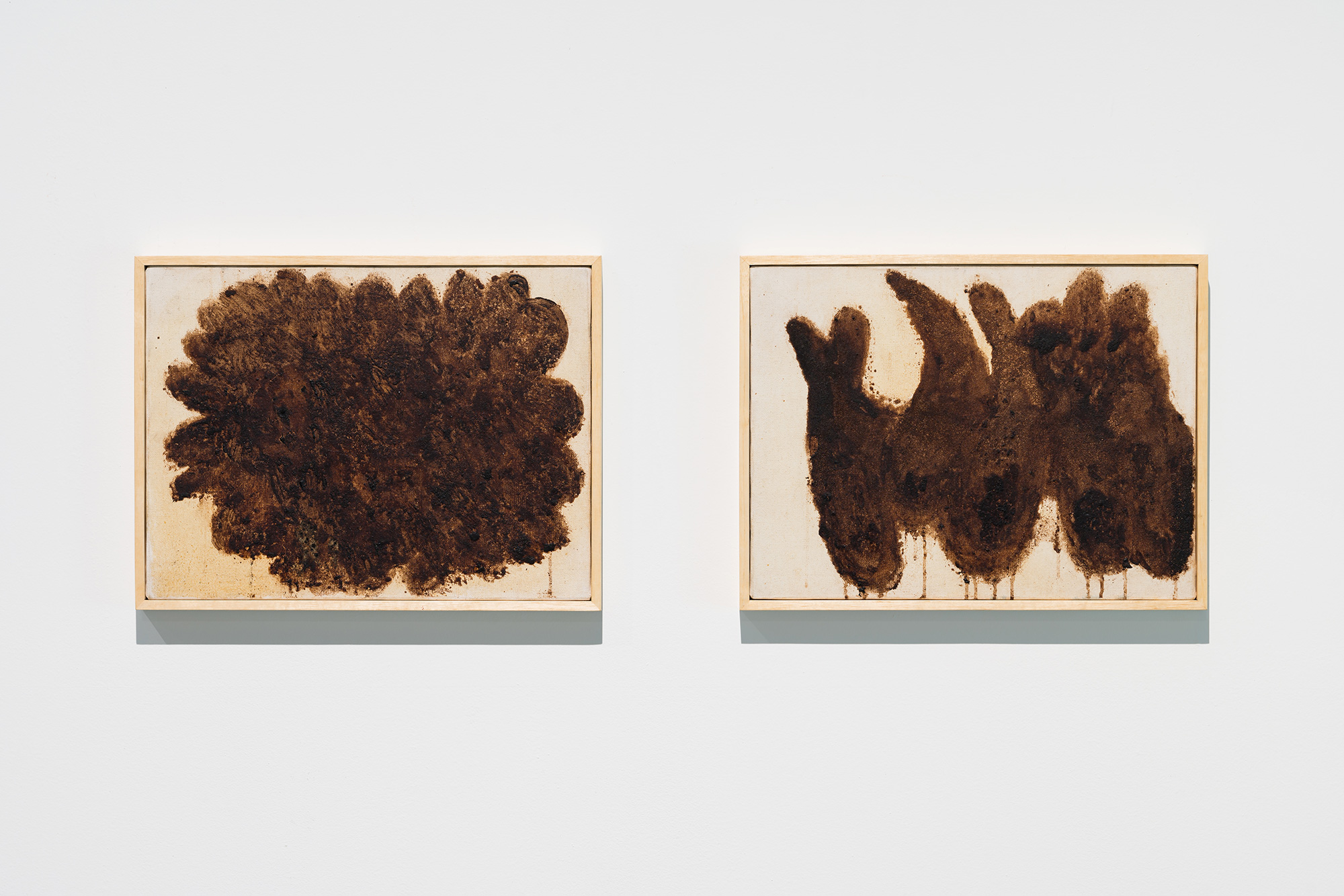

Solange Pessoa (*1961 in Ferros, Brazil) lives and works in Belo Horizonte. She works in a wide array of media from sculpture, installation, and ceramic to painting and video. Pessoa holds her degree from the Guignard School of Art at Minas Gerais State University, where she has taught sculpture since 1993. Pessoa has built an artistic career over more than three decades with a strong connection to the Brazilian Baroque tradition – one that does not resort to the use of anachronisms or the simple revisiting of a tradition that is very much embedded in the artist’s socio-cultural background. Pessoa received a grant from the Pollock Krasner Foundation (USA, 1996/1997), and has participated in numerous group exhibitions in Brazil and abroad.

Suzanne Husky (*1975 in Bazas, France) studied as Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux where she received an MFA. After studies in France, Suzanne moved to California and began to work on sculptures while documenting urban activism. It influenced her later works in which she questions how humans engage with nature, from earliest times till these days. Using all kinds of media like sculpture, photography, film, and installations, she examines relationships between plants, animals, and humans, and how we interact in a political and poetical way.

Uriel Orlow (*1973 in Zürich, Switzerland) studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design London, the Slade School of Art, University College London, and finally the University of Geneva, where he completed his PhD in Fine Art in 2002. His practice is research based and utilizes various forms of media, such as film, photography, drawing, and sound. Even with such a broad scope, he accomplishes to produce high quality works of art, such as his works “Memory of Trees”, “Wishing Trees”, “Theatrum Botanicum”, and “Soil Affinities”. These artworks focus on the plants as actors in history and as the silent witnesses.

The international group exhibition Planted in the Body continues the thematic direction of the explorative exhibition series Other Knowledge. This show looks into plants as sources and carriers of knowledge, and explores more precisely how the unique knowledge flora has been holding for centuries is transmitted. It highlights matrilineal and ancestral chains’ roles in preserving and passing down nature’s teachings. The latter are extremely diverse and touch on the realm of medicine, spirituality, survival skills, food practices, traumas and political memories.

The group exhibition Planted in the Body looked at soil, plants and their products – such as oils and pigments – as sources and carriers of knowledge and explored how their unique heritage has been transmitted through the centuries.

The exhibition aimed to be a celebration of vegetation in its own right, as it exists without human intervention and domination. Plants have been here before us and are likely to outlive us as well. It is us who are embedded within nature – and it far exceeds us. Yet, in this embedding, plants have also become crucial witnesses to human history, reflecting local, regional and global power struggles, as well as political and social divides, both in natural environments and human-made landscapes. Exploring plants and the transmission of their meaning places us in a liminal space where different forms of existence and knowledge overlap.

Planted in the Body highlighted the roles of matrilineality and kinship in preserving and passing down natural teachings that touch on the realms of remedies, spirituality, ecological care, survival skills, eating practices, gardening, mechanisms for coping with trauma, political memory and conflicts. The processes of transferring this knowledge are multi-faceted, ranging from verbal and nonverbal communication to oral traditions, storytelling, songs, practices and traditions transmitted and experienced through the body, rituals as well as intuition-based sensing of one’s surroundings. Whether we live in forests, on the plains or as desert nomads, or encounter vegetation in orchards, gardens and parks, we all experience a certain link with plants. They are part of us, but their knowledge is not always considered in proportion to their value, and fluctuates with time, culture and geography. Heritage chains are vulnerable and often at risk from threats such as disappearance and censorship. History provides many examples of the breaking of transmission chains, from rulers who regarded the knowledge of healers and herbalists as witchcraft, and ecosystems threatened by anthropogenic destruction, to younger generations losing their connection to their ancestors, to their land and to its nonhuman inhabitants. We need to care for such links, for it is through them that plants teach us not only about themselves, but more importantly, about ourselves.

At its core, the show endorses the notion of ‘plantcestors’, 1 Plantcestor: „an ancient living organism of the kind exemplified by trees, shrubs, herbs, grasses, ferns, and mosses, who live through absorbing water and the soil’s minerals through their roots, sunlight/starlight/moonlight/cosmic energy through their leaves, and the carbon-dioxide exhaled by humans and other mammals which they transform into oxygen. These beings are predecessors to the human kingdom, which depends on them to survive for food, breath, medicine, fire, shelter, and more. Through their intimate daily relationships to humans for many centuries, they have acted as vessels of ancestral, elemental, and *cosmic* knowledge, folklore, culture, history, and memory, and have been utilized to support the spiritual and earthly well-being of humans for many generations. They are our ancestor’s ancestors, amongst the earliest and most ancient beings whose livelihood, sacrifices, and brilliance has made human & animal life possible upon this Earth. Through intentional and reciprocal cultivation and respectful relationship with these diverse and multi-dimensional allies, humans have been able to access the masterful and mysterious healing miracles and deep wisdom afforded by these highly intelligent ancestors, towards greater alignment with our own authentic purpose, greater wholeness, peace, and balance with the natural order of the universe that ensures and sustains all life. This wisdom of “plants as ancestors” is practiced and tended by indigenous and traditional peoples from all over the globe, rooted in and passed down by the original ways of our ancestors.“ https://www.swanaancestralhub.org/what-does-plantcestor-mean because we believe that the non-linear knowledge carried by vegetation can also be accessed internally, without intermediaries, through the intimate bonds that we, as living entities, have established with the natural world – from seeds to leaves, bark, flowers and fruits. In a way, the know-how bestowed by the flora is planted in our bodies, as a gift that can be accessed through our intuition. Shared natural resources are our best teachers and our strongest allies in maintaining ecological balance. This is attested by indigenous knowledge and cosmogonies, which teach us how to receive messages from the vegetal, animal, mineral, spiritual and ancestral worlds, and to live in harmony with them, even if these voices have been weakened, discriminated against or otherwise silenced through imperial, colonial and capitalist domination. In this respect, many of the works featured in the exhibition adopt ethnobotanical ethics and envision regenerative practices for landscape, soil and body, thereby reconnecting us to our shared heritage.

Permeating the works are themes of fertility and seasonal cycles that connect us to both the abundance and decay present in all of us and lead us to question our own relationship to the patterns of transmission. If plants are mediators, then we should act as recipients of their heritage and learn how to integrate and act on it. Plants enable us to decolonize our ways of learning, preserving and passing down. The works included in Planted in the Body address all these issues while keeping in mind our common kinship and looking towards the future. We believe that listening to botanical knowledge leads us to embrace responsible ways of acting, being and resisting in response to our complex times when the exploitation of nature is an everyday reality.

Upon entering the exhibition space, the viewer can see from afar a painting by Aboriginal artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye (c. 1910–1996), before observing it in a more intimate manner. Her artworks deal with the power and vitality carried by plants and depict how women use the Australian atnwelarr plant (pencil yam) and native seeds, which allow for almost miraculous survival in the desert, and their relation to the ancestral landscape and cosmogony. Born in the Aboriginal community of Alhalkere in Utopia, Northern Territory, Kngwarreye was a member and custodian of the Anmatyerre community. She came to painting at a late age, focusing mainly on the Dreaming sites associated with the yam and women’s ceremonies. Her paintings Untitled (Alhalkere) and o.T. (both from 1993) are emblematic of the artist’s vibrant paintings of the plants and flowers used as food sources by the Anmatyerre community. Her color abstraction, filled with dots and lines, captures the world of arlatyeye (pencil yam), ntange (grass seed), intekwe (small plant), atnwerle (green bean) and kame (yam seed).

In a similar fashion, Solange Pessoa’s paintings made using genipapo (genipa americana) pigment in 2018 and her seven oils on canvas from 2020 also evoke ancestral heritage and represent a vibrant link to nature. Her compositions often recall historical cave art while also being inspired by Modernist aesthetics. In the exhibition, the audience could see her pieces featuring vegetal motifs, foliage and flowers made out of genipapo and lineaca – native oils and dyes used by indigenous Mineiro tribes for medicinal purposes and for body painting. Based in Minas Gerais, Brazil, Pessoa has been working with these pigments for a long time, learning from the indigenous women living in the area. In her work, the artist uses predominantly organic materials – soil, moss, feathers, soapstone, wax, seeds, etc. – transforming these earthy components into spiritual and metaphysical works that highlight our common kinship with the environment. Placing her paintings together with those of Emily Kame Kngwarreye fosters a dialogue between works that share the same approach and sensitivity, despite coming from distinct geographies, cultural contexts and time periods.

This deep connection to natural elements as sources of energy is also significant in Central Asia, as evidenced in Saodat Ismailova’s exploration of dendrolatry (tree worship) 2In the exhibition we accompany the video with an essay about dendolatry which you can download here http://www.meetfactory.cz/media/files/mf_saodat_en_web.pdf in the video Celestial Circles (2014), which was screened in the exhibition. It features women marching and chanting around a 300-year-old plane tree in Handoni Eshoni Chanor, Tajikistan. Tree worship – mainly of plane, elm and walnut – is widespread throughout Central Asia. Usually performed by women, it involves rituals, sacrifices, prayers and pilgrimages. In Celestial Circles, the camera spins hypnotically around the canopy, a motion that reveals a vegetal motif redolent of Uzbek traditional embroidery. In the exhibition, the video was projected onto the ceiling, physically immersing the viewer in the women worshippers’ pace of walking and singing. Another video by Ismailova, Chillpiq (2017), not exhibited in this show, reflects again on dendrolatry, although this time women walk around a tree-like metal pole on top of the Chillpiq mud tower, Uzbekistan, interestingly combining artificial components with a natural ritual.

Laura Huertas Millán focuses on one single plant, the coca plant, which, in the Muiná-Muruí community of Colombia, is traditionally a sacred guide for families and not merely a product. In her film JÍIBIE (2019), the artist depicts the fabrication ritual of green coca powder (called mambe or Jiíbie) and reveals an ancestral myth of kinship in which women and plants play a special role. Here, coca is considered not only as a source of knowledge but also a guide for discerning good from evil. Since 2018, Huertas Millán has been exploring the notion of the pharmakon (a plant that is both a poison and a remedy) and the non-human subjectivity of the coca plant, its uses in non-Western cosmology and its role in the so-called war on drugs and the prohibition of psychotropics. JÍIBIE allows the viewer to observe the traditional processing of the coca leaves by indigenous people (in contrast to the Western idea of cocaine as a white powder) while also exposing the colonial and postcolonial violence of conquest, exploitation and destruction of indigenous traditions and knowledge.

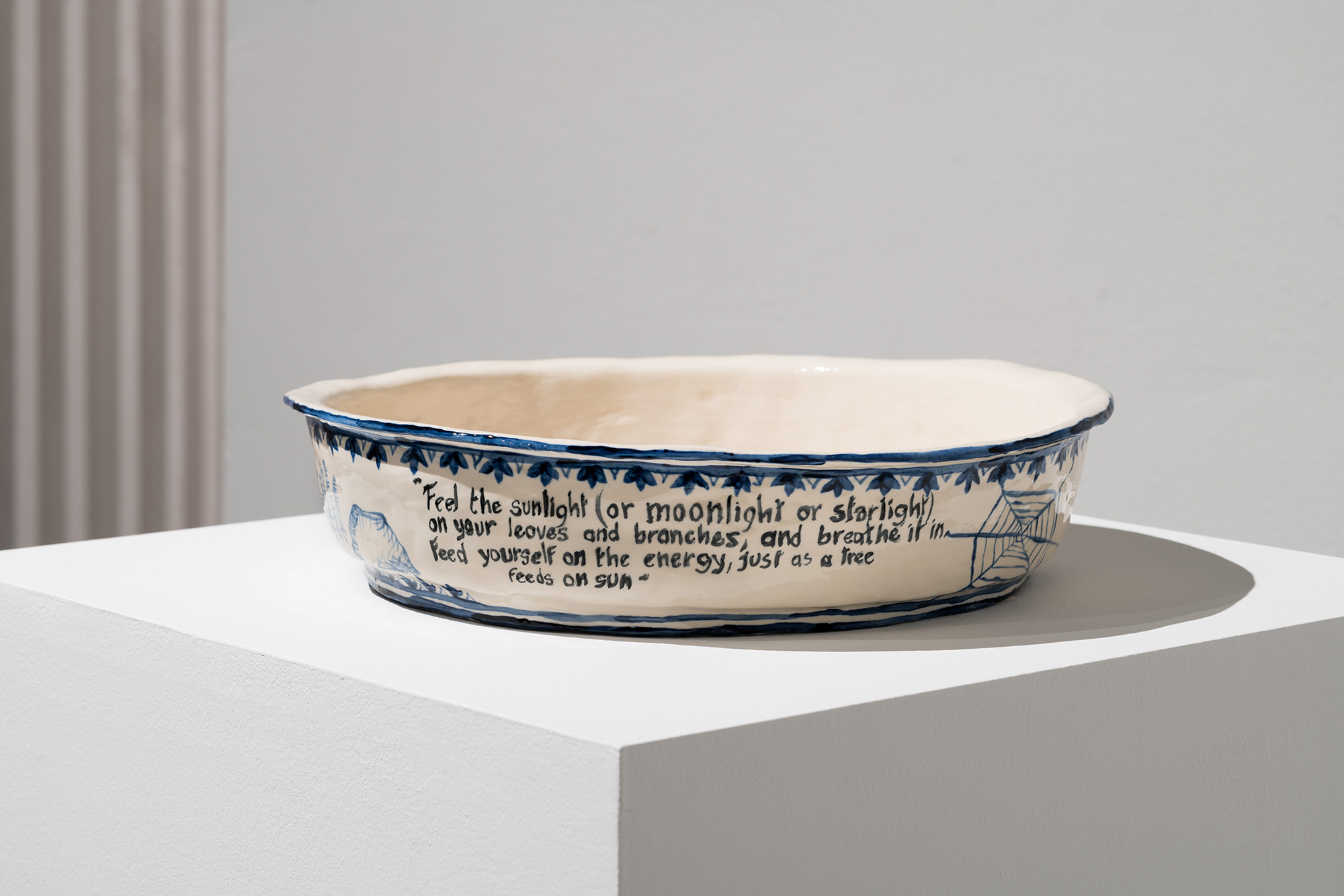

Likewise, Suzanne Husky is interested in natural remedies that can teach as well as heal. In her multimedia practice, Husky combines handmade objects and crafts with research in botany, agriculture and history, with a strong component of ecological awareness. Her large series of ceramic objects Apothecary Pots. Plancestors (2019) – from which we presented a jug and a (wash)bowl – is inspired by the traditional blue-and-white design of the albarello (medicinal jar) produced in 15th-century Italy, based on examples brought by Hispano-Moresque traders. The drawings on these pots depict people (mainly women) and plants or fungi hybrids and proclaim the interconnectedness of life, as well as our responsibility as ancestors to our descendants. Talking about this series of pots, Husky contextualizes her intentions and interests: “I’m taking a ‘Herbal Allies’ class at Oakland’s Ancestral Apothecary School where plants are our allies, ancestors and teachers if we listen to them. Each week begins with a meditation where we become plants. Then, with our eyes closed, we lick a few drops of tincture from the back of our hand and observe their movements in our bodies, their effects on our thoughts. We share our intuitions and our visions, and we are here but also with our ancestors who knew these plants and used them.”

As a complement to her work, Suzanne Husky also created a new episode of her (French-language) podcast series in which she interviews the Franciscan friar and agricultural engineer Hervé Coves and discusses the significance of various plants in Czech (and Central European, more broadly) tales and myths.

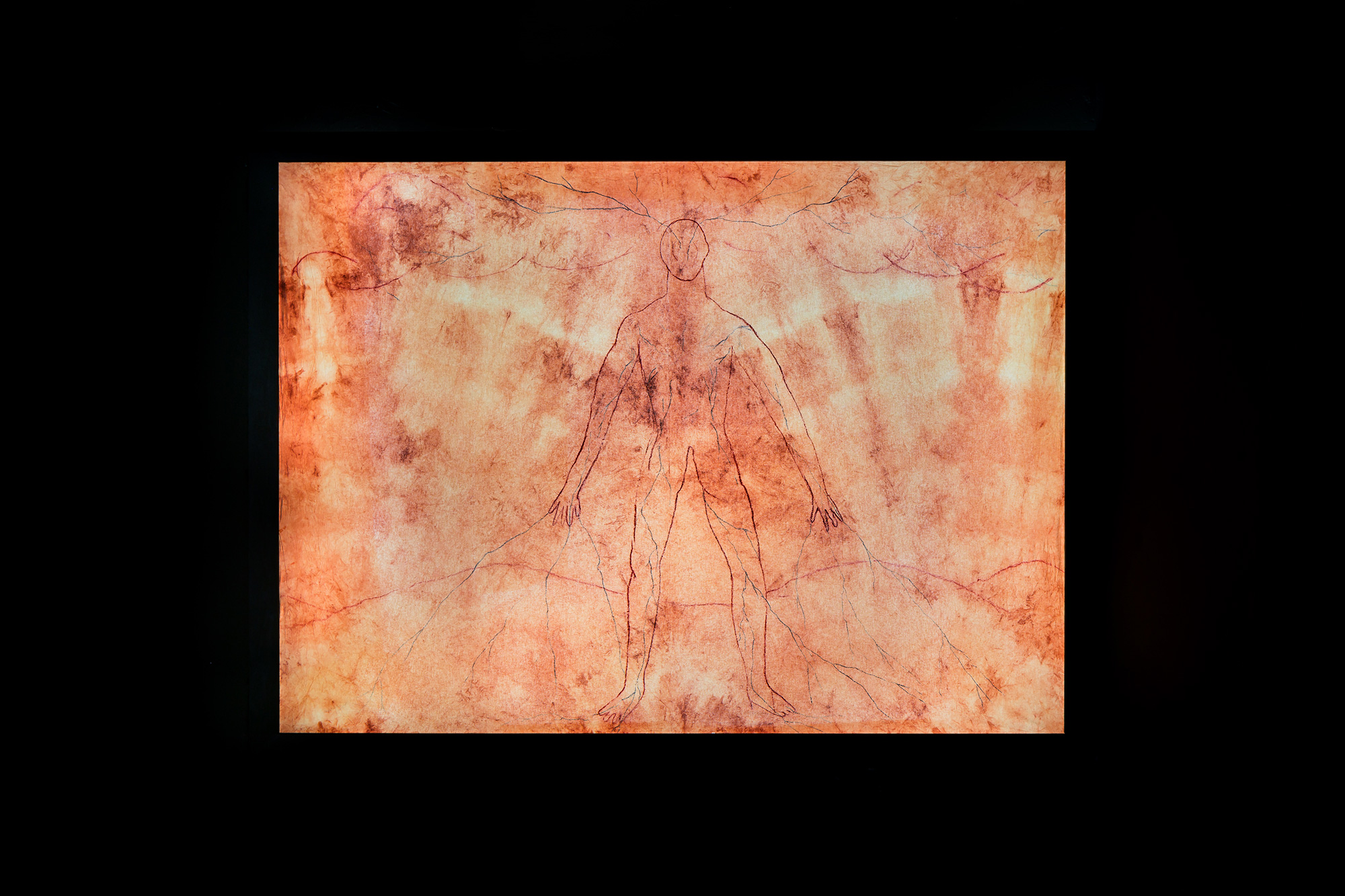

The notion of human and non-human ancestry is also present in the current works of Adéla Součková, who has long been inspired by her extensive research into history, mythology and cosmogony. In Planted in the Body we presented her painting Connected (2021, from a larger series), which depicts an androgynous human body rooted in the ground and simultaneously interwoven with the sky. Like the figures of Suzanne Husky, Součková’s painting shows the interconnectedness and dependency, both material and spiritual, of human beings and the environment. Součková uses various natural pigments to dye her canvases, such as onion, wine/grapes or ash from various sources. For the background of this painting, she used madder root, which she discovered during her stay in Georgia, where it has a number of both religious and worldly uses. 3On Good Friday, Orthodox Christians in Georgia dye hard-boiled eggs a red color using the root of the madder plant and onion peel. The eggs represent the blood of Christ and are placed on green wheat grass, which symbolises new life, resurrection and eternity. – https://georgiaabout.com/2014/04/18/dyeing-eggs-red-for-orthodox-easter/ Madder root (rubia tinctoria) has been used for thousands of years as a textile dye, imparting orange and red tones to fibers, the oldest examples of which were discovered in archaeological sites in India and Egypt.

Alongside Connected, we exhibited a collection of older series of works by Adéla Součková, Pregnant with Ancestors and Pixeled (2019). These are lightboxes depicting another traditional way of dyeing fabrics – Moravian blueprint. Originally, a natural indigo (plant-based) pigment was used for blueprint, which was eventually replaced by synthetic indigo. Součková often works with archetypal symbols or updated versions thereof – here, the motif of a pregnant woman with heads/masks inside her body can be seen as a mother-goddess figure, a celebration of fertility (which, in general terms, connects the woman’s body with the Earth and its cycles), or as an expression of the ancestor–descendant relationship.

Luiza Prado de O. Martins delves further into women’s bodies by unravelling the links between plant knowledge, fertility and abortion, sometimes touching upon the complex and traumatic (post)colonial experience. She has created two new works for the exhibition, both following up on her earlier projects and research. In Notes to the Seers (2021), the artist tells us about two plants found all over the world, wormwood (or artemisia) and rue, both of which have a long tradition of use as remedies (especially for “women’s illnesses”, to stimulate the menses or relieve menstruation pains), but also as a sacred protectors from harm. The story of artemisia is framed within Greek mythology, whereas the story of rue is told from a very personal point of view, connecting the artist with her Brazilian origin and traditions. Visitors could take envelopes of the herbs, experience their smell and taste, ideally in the form of a decoction, and thus experience them physically through their own bodies and senses. The stories are also available in the form of an audio recording.

The second exhibited work by Prado follows up on her earlier project Between The Beginning of Sense and The Chaos of Feeling: A Multispecies Banquet (from 2019), which also used plants as ingredients – specifically those that are used both as food and in herbal preparations meant to induce fertility and lust. These ingredients were used for dinners served on bioplastic plates that afterwards preserved the traces of both human and non-human meal companions. The exhibited resin panels, titled Fleeting Commensalities (2021), preserve these leftovers, expressing once again the idea that humans, plants and all other creatures are part of a complex, entangled chain of life.

Nikola Brabcová and Alexandra Cihanská Machová created a new multimedia installation that combined Nikola’s objects and video with Alexandra’s soundscapes. Nikola Brabcová based her work on her long-term interest in soil and environmentally-friendly ways of producing artworks. In her Jara installation, she used natural materials (including bioplastic) that are biodegradable and have minimal impact on the environment. Her artistic work occurs alongside her everyday life, housework, cooking and parenting. Therefore, she recycles and uses ordinary materials, even leftovers. She strives to produce something ephemeral and indefinite, a sculpture that attests to the process of its own creation. Alexandra, whose work acted as connective tissue between the video and the objects, perceives sound as a vibration that goes through our bodies/matter and alters us. At the same time, the deliberately intrusive presence of cables and other technical devices reminds us that technology (and media such as sound or video) is not immaterial but has a strong impact on our environment. In her video, Nikola shows an ordinary walk through the garden of her mother-in-law. There, the grandmother explains to her grandson where food comes from, the different roles played by insects and weeds, how composting works and also how crucial the legacy of previous generations is – represented here by the trees planted by the grandfather. The aim of this video is to think about forms of agriculture and farming driven by the love of nature (rather than its exploitation) in which personal experience and sensitive knowledge foster a respectful relationship towards plants.

In the video Flames Among Stones (2019), Corinne Silva looks at gardening as a resistance strategy, giving us access to a walled women’s garden in Central Turkey and contrasting it with the authoritarianism and patriarchy that exists beyond it. Set up by two sisters, Güler and Türkan, this plot of land is a haven, a fertile ground for entering into resonance with the Earth and its knowledge. Responding to the dictates of climate, and gently letting nature indicate the path to take, the gardeners follow seasonal rhythms and return to a circadian time. Through organic gestures, they work with the soil, not against it. By weaving the folktale of Şahmaran, a deity with the head of a woman and the body of a snake who holds knowledge of all realms, Silva also explores matrilineality and how one can cultivate and value the knowledge of the earth. Gardening thus becomes a passageway to another sort of wisdom which helps us re-ground ourselves and respond to exclusionary politics and ecological degradation. Her imposing, nine-meter-wide textile work, All Our Mothers’ Gardens (2021), represented a transition towards video installation and occupied a prominent place in the gallery’s main room. The piece integrates fabrics dyed with dirt and plants from a number of community, memorial, allotment and guerrilla gardens, including the community-led Parko Navarinou (Exarcheia, Athens), Granby Four Streets Community Land Trust (Liverpool) and Extinction Rebellion’s community garden (London). To push through the hanging veil of the textile and enter the video installation space is to cross a threshold into a world of non-patriarchal knowledge transmission, one that privileges women’s, non-Western and more-than-human wisdom.

Uriel Orlow’s contribution to the exhibition presented trees as witnesses to important historical events as well as sources of energy – as contributors to the healing processes on the Mafia-infested Sicily and as bearers of memories tied to colonial influence in South Africa. We exhibited Orlow’s project Wishing Trees (2018), an immersive multimedia installation that is part of his larger work Theatrum Botanicum, a thorough exploration of botanical politics. Here, he emphasizes the role of plants as carriers of political memory, especially memory tied to power distribution and conflict. The multiple layers of Wishing Trees are connected to three Sicilian trees connected with the history of activism and migration. The first is a 440-year-old cypress outside Palermo linked to San Benedetto il Moro; the second is the fig tree in the center of Palermo, overlooking the residence of the murdered judge Giovanni Falcone; and the third is an olive tree under which the armistice ending Italy’s participation in World War II was signed. These trees are thus reminders of stories of slavery, religion, cooking and migration, as well as the fight against the Mafia and the first resistance against it, led by women activists, and memories of war. Through this piece, Orlow stresses how intertwined the fates of nature and humans are.

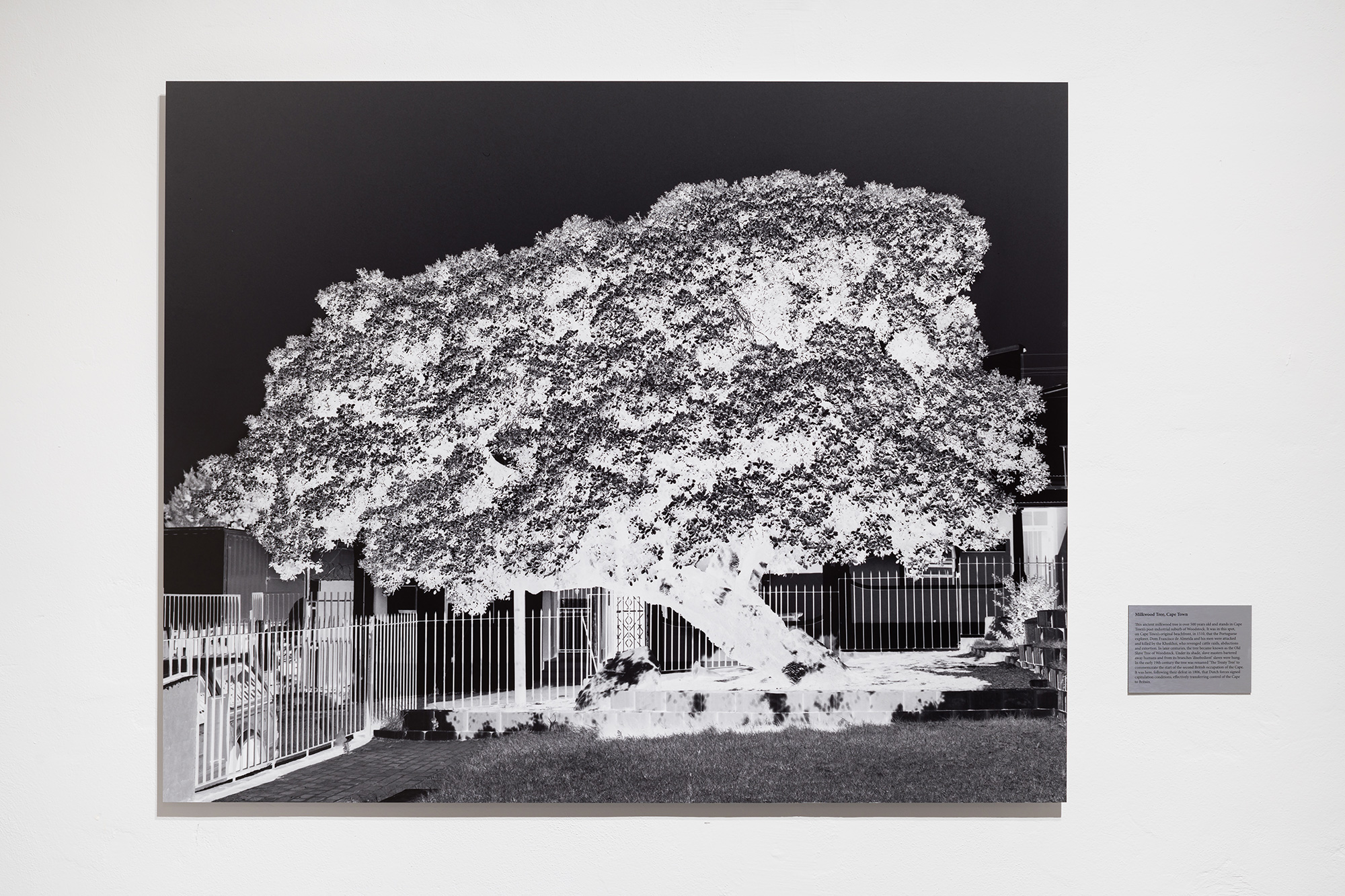

Second work by Orlow in the exhibition is a photograph from his series The Memory of Trees (2016), which deals with the importance of plants as geopolitical movers in and as holders of memories and traces of history. The series consists of five pieces focusing on South Africa and trees linked to the Dutch colonial past and to apartheid, as well as on the complex history of the plant trade and the plundering of plants.

The exhibition Planted in the Body was marked by the strong architectural motif of a circle connecting all parts of the space and symbolically representing a tree trunk which the visitor could enter. All the artworks, in their diversity of media, techniques and styles, resonated together on many, sometimes unexpected, levels, which were revealed during the installation process. The predominant use of raw, non-polluting vegetal matter runed through several pieces, and, in others, a link emerged between the figure of the grandmother (or a woman ancestor) and her (great)grandchildren. The evidence of the power infused by plants into our daily lives jumped out at us – curators, artists and viewers. We found that in their materiality and form, as well as in their content, the new commissions – subconsciously, through our curatorial frame – became symbiotic fellows to the older works. The different generations of artists entered into dialogue, and, despite coming from various cultural contexts, they showed how the knowledge of plants courses through our bodies and our senses, without intermediaries, and stressed how interconnected our human existence is with that of natural entities. Absorbing such knowledge through embodied practice opens us up to grasping the cyclical, transient and regenerative nature of all things. Again, we are within nature and nature is within us.

Interview with the exhibition curators about the knowledge carried by plants and its transmission within the matrilineal tradition, about how we care for plants and how they take care of us.