Wells of Wisdom

Alina Szapocznikow (*1927 – †1973) was a Polish sculptor who studied at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague and at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris. She came back to Poland in 1951 and began to participate in artistic life, taking part in competitions to create public monuments of the Warsaw Heroes, the victims of Auschwitz, and Juliusz Słowacki. In 1963, she moved to France for good. In Paris, she became involved with the Nouveau Réalisme movement, led by the critic Pierre Restany. Szapocznikow retained her originality, remaining a sensitive artist focused mostly on issues of intimacy and body. She was one of the first artists to work with innovative materials like polyester and polyurethane, and these new sources enabled her to not only develop a distinct visual language but to also come to terms with the pain she experienced as a child and its lasting physical and psychological imprint. Szapocznikow represented Poland in the 1962 Venice Biennale, and in 2012, she was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Aline Bouvy (*1974) lives and works in Brussels and Perlé. She studied at the Ecole de Recherche Graphique in Brussels and at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. The sculptures, objects, and installations that originate from her remarkable practice are difficult to pin down. Bouvy does not restrict herself to a routine use of defined “disciplines” and techniques but explores both the limitations and the possibilities of the most diverse media. Her work is available on display in multiple galleries recorded on Artland. These galleries include Damien & The Love Guru, Komplot, and Baronian Xippas in Brussels.

Anna Daučíková (*1950) is a Slovak visual artist and activist based in Prague and Bratislava. In the 1980s, they studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava. After graduating, they moved to Moscow in Russia. After returning to Bratislava in 1991, they co-founded the Slovak feminist cultural journal Aspekt. Throughout the 1990s, they experimented with the representation of sexuality depicted in the medium of video, often combining video screenings with live performances. Daučíková is one of the first Slovak artists to openly identify as queer and engage with feminism. They have exhibited at a number of major international exhibitions, including “Gender Check” (2009–2010) at Mumok Vienna and Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. In 2018, they were the winner of the Schering Stiftung Art Award and had a solo exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin.

Esther Ferrer (*1937) is a Spanish artist mostly known for her work as a visual artist, but also for her performances, either alone or within the Spanish group ZAJ. Since the 1970s, part of her activity has been devoted to fine arts, such as reworked photographs, installations, paintings according to a series of prime numbers, objects, etc. As a performer, she has participated in festivals in Canada, Korea, the United States, Japan, and throughout Europe. Her production also includes objects, photos, video pieces, visual systems based on prime numbers, and a large collection of self-portraits in many media. Ferrer represented Spain in the Venice Biennale in 1999 and did large individual shows in subsequent years in the FRAC Bretagne–Rennes in France.

Eva Kmentová (*1927 – †1980) belonged to the first post-war generation, which in its youth overcame a particularly difficult section of the Czech modern history. She studied at the Academy of Arts Architecture and Design in Prague. In the 1960s, she quickly became one of the most interesting personalities in Czech fine arts and is still considered one of the protagonists of the Czech “new wave” in art. Kmentová is known mainly as an author imprinting segments of the human body into plaster. In addition to sculpture, she also engaged in drawing, collage, and paper assemblage. Kmentová exhibited independently in 1963 in the Aleš’s Hall – Gallery of the Youth and in 1989 to a greater extent. Her work was exhibited in the National Gallery in Prague.

Jana Želibská (*1941) is a Slovak painter, sculptor, pedagogue, performer, and video artist. From 1959 to 1966, she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava and she undertook a study trip to Paris in 1968. In her work, she devoted herself to various artistic expressions. Želibská participated in the beginnings of environment art and object in the 1960’s, action and concept in the 1970’s, postmodern object and installation in the late 1980’s, and video art in the 1990’s. She was the only member of her generation who openly dealt with intimate relationships between men and women, and “celebrated” the female body from the (proto-)feminist perspective. From the very beginning, she addressed the issues of sensuality, sexuality, and eroticism. At the Paris Biennial of Young Artists, Želibská presented her “Taste of Paradise” installation (1973). She hung a golden apple high in a tree beyond the reach of hands as an embodiment of forbidden knowledge.

Julie Béna (*1982) lives and works in Prague and Paris. She is a graduate of the Villa Arson in Nice and attended the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. Her work is made up of an eclectic set of references, combining contemporary and ancient literature, high and low art, joking and seriousness, parallel times and spaces. Comprising sculpture, installation, film, and performance, her work often seems to float in an infinite vacuum, unfolding against a fictional backdrop where everything is possible. In 2012–2013, she was part of Le Pavillon, the research laboratory of Palais de Tokyo. In 2018, she was nominated for the Prix AWARE Women Art Prize. She is represented by the Joseph Tang Gallery in Paris and Polansky Gallery in Prague.

Kris Lemsalu (*1985) is a contemporary artist based in Tallinn and Vienna. She studied art at the Estonian Academy of Arts, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Lemsalu merges animals and humans, nature and culture, and abjection and beauty in her sculptures, installations, and performances. Her works are composed of found and handmade materials, including animal pelts, clothing, and food, and are centred around ceramic objects made by the artist, reflecting her training as a ceramist. Maximalist, visceral, and sexualized, Lemsalu’s pieces evoke the wild, bestial side of human beings and civilizations, and are underscored by feminist themes. Her work has been shown in many places, including Berlin, Copenhagen, and Tokyo. In 2015, she participated in the Frieze Art Fair New York where her work “Whole Alone 2” was selected among five best exhibits by the Frieze New York jury.

Marianne Vlaschits (*1983) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts with Professor Gunter Damisch and also attended the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Her work deals with consummate beauty and felicity, using the human body as a building block towards the creation of artificial paradise. While she primarily creates paintings and installations, Vlaschits has extended her artistry to video and performance art. Vlaschits’ interest in astronomy is evident in her works. It often deals with extra-terrestrial life and outer space. Her works are also reflections on gender, utopia, human existence, and the future. Vlaschits said she was inspired by the thought of a utopian society where its inhabitants are not bounded by gender, sexualities, and bodies. Her work has been shown in many places, including Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, La Musery in Vienna or Salzburger Kunstverein.

Marie Lukáčová (*1991) is a Czech visual artist. She got her Master’s degree at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague in 2017. She is one of the three founders of the Feminist Group / FB Guerilla called “The Fourth Wave” which launched a public debate about sexism at universities in 2017. Marie also participated in the establishing of the critical-student organization “Studio without Master”, where she worked and studied from 2015 to 2017. She also studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno and at the Art Academy Mainz in Germany. Lukáčová had her first solo exhibitions in 2014, and since then, in addition to her relatively large participation in group shows, she has had them every year. In 2019, she had a solo exhibition “Sirena Bona” in GAMU Gallery in Prague.

Romana Drdová (*1987) is a Czech visual artist. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 2017. She also went on several study stays, e.g. at the Korean University in Seoul and at the studios of visiting professors Florian Pumhösel and Nicole Wermers at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Her work, often in the media of object, photography, and installation, is characterized by its pure aesthetic, often even transparency, and use of light, matter, and emptiness combined with specific materials and techniques inspired by the context of visual arts as well as the world of fashion, technology, and design. Drdová has introduced her work primarily at Czech independent institutions (solo exhibitions at Prague’s MeetFactory and Karlin Studios) as well as at the National Gallery in Prague and in the international context in Vienna, Berlin, and Liège.

Toyen (given name Marie Čermínová, *1902 – †1980) was a Czech painter, drafter, illustrator, and a member of the surrealist movement. In 1923, the artist adopted the professional and gender-neutral pseudonym Toyen. Toyen joined the Czech avant-garde group Devětsil in 1923 and exhibited with them. The group had strong international connections, especially but not only with French culture. In 1925, Toyen went to Paris where they and their colleague painter Jindřich Štyrský announced their own direction called artificialism, characterized as lyrical and dreamy semi-abstraction inspired by personal memories. Toyen is also known for their open depiction of erotic motifs and erotic humour.

Veronika Šrek Bromová (*1966) lives and works in Prague. She studied at the Academy of Arts Architecture and Design in Prague. She began exhibiting in the early 1990s and soon became one of the most sought-after artists of her generation. She enriched the new art scene with bold experiments using new technologies. She researched the parameters of shame. Her works are uncompromising and capture a deeply personal and intimate artistic expression. At the heart of her work are feminine themes, body, family, alternative family, nature, mythology, psychology, and recently, she is developing her own ways of a ritual. Bromová has exhibited in many places in Europe and the USA. She represented the Czech Republic at the Venice Biennale in 1999. Her works are in major public collections in the Czech Republic and Europe.

Yishay Garbasz (*1970) is an Israeli interdisciplinary artist who works in the fields of photography, performance, and installation. She studied photography with Stephen Shore at Bard College between 2000 and 2004. Garbasz received the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship in 2004/2005. She has lived in Berlin since 2005 and has also lived in Taiwan, Thailand, Japan, Korea, Israel, the USA, and England. Her main field of interest is trauma and the inheritance of post-traumatic memory. She also works on issues of identity and the invisibility of trans women. Her works have been exhibited in solo and group shows in galleries and museums internationally including Tokyo, Seoul, New York, Miami, Boston, Berlin, Paris, London, and at the Busan Biennale.

Zackary Drucker (*1983) is an American trans woman multimedia artist, cultural producer, LGBT activist, actress, and television producer. In 2007, Drucker graduated from California Institute of the Arts. She is an Emmy-nominated producer for the docu-series This Is Me and a consultant on the TV series Transparent. Drucker is an artist whose work explores themes of gender and sexuality and critiques predominant two-dimensional representations. Drucker has stated that she considers discovering, telling, and preserving trans history to be not only an artistic opportunity but a political responsibility. Drucker’s work has been exhibited in galleries, museums, and film festivals including but not limited to the 2014 Whitney Biennial, MoMA PS1, Hammer Museum, Art Gallery of Ontario, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern art.

The exhibition Wells of Wisdom attempts to answer the question of how our corporeality influences our understanding and experience of the world, and how the body itself can be a source of knowledge. The notional well of wisdom of the exhibition title includes richness and knowledge that exceeds the gender identities of the cis and trans women who are mostly represented in this exhibition. Each of us has an experience acquired through corporeal experience, but even so, it cannot be described as universal – not even within a single gender. Despite this fact, we search for what connects the exhibiting artists in the context of corporeality, without calling their individuality into question. More than biological processes and experiences that are tied to changes in the body, experiences of cyclicity, or pain and pleasure, we witness the arising of social connections. We realise that the inequalities we experience are not caused by our bodies, are not natural (or, on the contrary, unnatural or “deviant” if they defy binary gender norms). The difference of our bodies from the “neutral” patriarchal body, however, allows society to legitimise and normalise these inequalities.The exhibition therefore wants to be a space in which to reflect upon the vulnerability of our bodies, which is not determined by a supposed fragility or weakness but by the hostility of an androcentric world. It is also, however, a celebration of their vitality and beauty by combining historical works from the 1930s with completely contemporary works, creating a unique and mutually enriching dialogue across generations.

“These last years, I saw blogs around vulvas emerging, I saw images and pictures of their plurality. I saw cis women, non binary people, trans people, intersex people, gendernonconforming people, gender fluid people having access to this. And this is not ridiculous, and this is not nothing, and this is not a joke.

These last years, I saw people with vulvas taking their “shaming” genital apparels for centuries and empowering it: not being shy anymore, not being ashamed anymore, not being muted anymore. And this is not ridiculous, and this is not nothing, and this is not a joke. And I am so happy to witness this! and relieved to see these differences, these multiplicities, these complexities, stepping out from the norm, this norm that is so strong and humiliating. So when after centuries of negation and ignorance, for the first time, we are taking in consideration the genitals in their pluralities, finally hearing, recognising and giving name to pain, suffering, pleasure, and love, visualizing what is happening inside our own body, I am wondering what this show is about?” – J.B.

The exhibition Wells of Wisdom attempted to answer the question of how our corporeality influences our understanding and experience of the world, and how the body itself can be a source of knowledge. 1At this point, it is appropriate to note our own position as white, middle-class, heterosexual cis women. We begin from the experience that, in a patriarchal society 2By patriarchy we mean the domination of men across the world – not just over women but over the structure of social relationships in general. (in which we’re still living – we’re not talking about the Middle Ages here!), the body that is perceived as socially neutral, primordial, “Adamic” and therefore naturally superior, is the body of the cisgender man. What we are interested in, however, is the experience and knowledge of bodies that this perspective views as “other”, as marked. However, we do not wish to perpetuate a binary logic by describing these bodies merely as those of women. The notional well of wisdom from the exhibition’s title includes a richness and knowledge that exceeds the gender identities of the cis and trans women making up most of this exhibition.

Each of us has a set of lived experience acquired through our bodily existence, but even so, it cannot be described as universal – not even within a single gender. Despite this fact, we search for what connects the exhibiting artists in the context of corporeality, without calling their individuality into question. More than biological processes and experiences that are tied to changes in the body, experiences of cyclicality, or pain and pleasure, we witness the arising of social connections. We realize that the inequalities we experience are not caused by our bodies, are not natural (or, on the contrary, unnatural or “deviant” if they defy binary gender norms). The difference of our bodies from the “neutral” patriarchal body, however, allows society to legitimize and normalize these inequalities.

The exhibition therefore aimed to be a space in which to reflect upon the vulnerability of our bodies, which is not determined by their supposed fragility or weakness but by the hostility of an androcentric world. It was also, however, a celebration of their vitality and beauty. A majority of the exhibited works focuses on the most intimate parts of the body, which we see as imprints of the artists’ individuality as well as striking symbols – gates to the wisdom of our bodies, nodes of pain and pleasure, spaces of joyously giving ourselves over to others as well as spaces of plundering and violence. These are parts of our bodies that we must expose or cover up against our will.

The exhibiting artists share a particular openness with which they approach the experience and knowledge of the body, accepting it (or attempting to do so through their work), examining it, and reporting on it. It was important for us to combine the works of artists across different generations into a single living organism, turning to the body as a source of knowledge about the self and the world around us from various perspectives and positions, but always with certainty and self-confidence. The curatorial intent in including (iconic) historical works, however, was not to create a sequential “genealogy” of creative approaches and positions within which the new follows up on the old – rather, we wanted to recontextualize the works of the past, and, by linking them to and confronting them with the works of today, create a reinterpretation that goes both ways.

The entirety of the exhibition was connected by a striking curatorial vision of exhibition architecture, made possible in collaboration with the architectural duo Stibitz & Stibitz, and complemented by new works from Marie Lukáčová, made specially for the exhibition. Lukáčová’s approach, which represents a long-standing endeavor to attain emancipation and reclaim the representation of the woman’s body with disarming honesty and humor, is, in many ways, emblematic of the exhibition. The semi-transparent curtain through which we entered the exhibition immediately connects the motif of the vulva (and, by extension, the body as a whole) with the motif of the eye or, more precisely, its gaze. It uses clear symbols to remind us of the dialectic within which our bodies (and vulvas) are both seeing and exposed to the gaze.

“There was this thing that happened to me. Suddenly, my body got blown up a good forty kilos and then deflated back to its original size. All this during two and a half years. That is, in itself, quite a process of transformation – not to mention that during that weight peak, my body even managed to generate a little dude. Great love, no sleep, lots of work. During this process, I began to be visited by images. Visualities. Even before then, I’d worked a lot with my dreams, but it was now as if these dreams were “happening” to me during the day. Out of the blue, I get a very pleasant chill and goosebumps. A small orgasm, haha, that shows me a story or narrative. And then I just draw that from memory.

When you travel through such a variety of forms with your body, it allows you one thing – to consider problems from several perspectives. As a stressed-out mother, a chilled-out girl, someone who can’t fit in their pants, and someone racked by FOMO. You can suddenly laugh at your feelings, your addictions, and the obstacles that you face daily. I suspect that my personal wealth will one day end and I’ll settle down in one of these roles, but until then…” – M.L.

The first work we encountered upon entering the gallery was a hand-colored illustration by Toyen. It depicts a woman putting a mirror up to her genitals. In 2021, Toyen’s gender identity was the subject of heated discussions in relation to a major retrospective dedicated to the artist at the National Gallery in Prague. We cannot know for sure how Toyen would identify if they had the opportunity to adopt today’s designation as trans or non-binary. The fact that their sexual orientation and gender identity defied both heteronormativity and cissexism, however, is clear both from their biography and from their oeuvre. Furthermore, their work is also strongly permeated by an interest in corporeality. This is why including Toyen in the exhibition – though only in the form of bibliophilia 3These are illustrations that might seem secondary in the context of Toyen’s fine art pieces. However, as the art historian Ladislav Zikmund Lender points out in his article for artalk.cz, illustrations can also contain highly personal testimony. See https://artalk.cz/2021/06/14/i-am-not-your-lesbo-k-diskurzu-o-soukromi-snici-rebelky/ – was essential for us, as the legacy of both their work and them as a person remains highly topical. Is the woman in the illustration examining her body or baring it to the world? Is this a gesture of self-knowledge. of seduction, or is it an accusation of those around her, who see only this one part of her?

The piece by Yishay Garbasz comments on this reduction of personality to genitalia openly and from the most private of perspectives. She invites us to closely examine the detailed imprints of her naked body before and after gender confirmation surgery. The process of transitioning, or rather, of becoming who she always actually was, is also closely documented in an extensive series of photographs collected in a flip book, where rapidly flicking through the pages creates a simple animation. On the one hand, Garbasz reveals something from the life of trans people that the public, with their tabloid thinking, have always wanted to see whole, on the other, she also alerts us to the absurdity and incorrectness, or more precisely, violence, that is connected with this approach. As we thumb through the flip book, we can focus on the artist’s chest and groin, or we can choose to focus instead on her hair and its continuity across time. Though, in some respects, her body changed dramatically over the course of two years, she remains the same person.

Anna Daučíková’s video We Care About Your Eyes turns our attention right between the legs, directly and uncompromisingly, but what we are confronted with there is a mirror’s reflection. In a gradually quickening rhythm evocative of masturbation, it reveals the fragments of its surroundings, including hints of (another) body and, finally, the lens of the camera itself, which has been the embodiment of the objectifying gaze since the 70s, thanks to theorist Laura Mulvey. In the context of Anna Daučíková’s non-binary gender identity, another element that is highly important for reading the video is the ambivalence of bodily suggestions that the reflection shows in their own crotch. Here too, then, a crucial role is ascribed to the process of seeing and making visible – including, in particular, that which has somehow been banished from the field of vision.4 “According to the theoretical texts, one first turns the camera onto themself. But I did not need my own face at all – I started with a close detail of hands. These were my hands, the things which create the action. Close detail was also a means for me to evoke intimacy, which automatically invited in a sense of embodiment, eroticism, and sexuality. I engaged with corporeality as a visualization of desire. I wanted to achieve a particular form of obscenity that I consider positive in the sense that it is banished off stage and brings itself to the center of the spectator’s attention. The obscene is pushed out of sight but returns to the stage through my decision. […] I believe that visual pleasure is everywhere, and that pleasure need not be genital and erotic. It is the pleasure of seeing.” – Anna Daučíková in an interview for Art+Antiques, March 2015.

It is no coincidence that we situated Julie Béna’s chandelier made of glass vulvas near Daučíková’s video. Daučíková described the connections between glass and video (which is also the medium that Béna uses in another part of the exhibition) as follows: “After I finished my studies, I abandoned glass making, but the experience of this non-material remained inside me, as well as a particular form of spirituality that arises from this optical experience of a subject that observes – and it is no longer merely looking but gazing. That is one internal connection between video and my early days of working with glass. And mirroring, too. Only once I was already making videos did I realize that I know this and feel close to it, the narcissistic perspective of the subject who can only know themself in the mirror. I can only say I when I see You, or rather the Other, which both is and isn’t Me and is looking at me.”5Anna Daučíková in an interview for pro Art+Antiques, March 2015. Julie Béna created a truly symbolic object that brings together spiritual connotations (we are literally “illuminated” by the glass vulvas) with the polyvalence of a medium that is both transparent and reflective.

The works of Veronika Šrek Bromová are closely tied to corporeality in an explicit, material, almost raw form. Her provocative and at the same time iconic image of a cross-section of her own torso from the Pohledy (Views) series was, on this occasion, complemented by an original, unedited photograph. Bromová, whose openness in working with her own body was perceived by many in the 90s as shocking, took approximately twenty years before finding the resolve to show an entirely uncovered view of herself. By placing them in a narrow corridor, we wanted to further amplify the urgency and resoluteness of these photographs. Our aim was not to shock (though shock might form part of the spectator’s experience) but to emphasize that this gesture by the artist is meant to be seen – that it is a gesture of liberating self-acceptance that both inspires and challenges us.

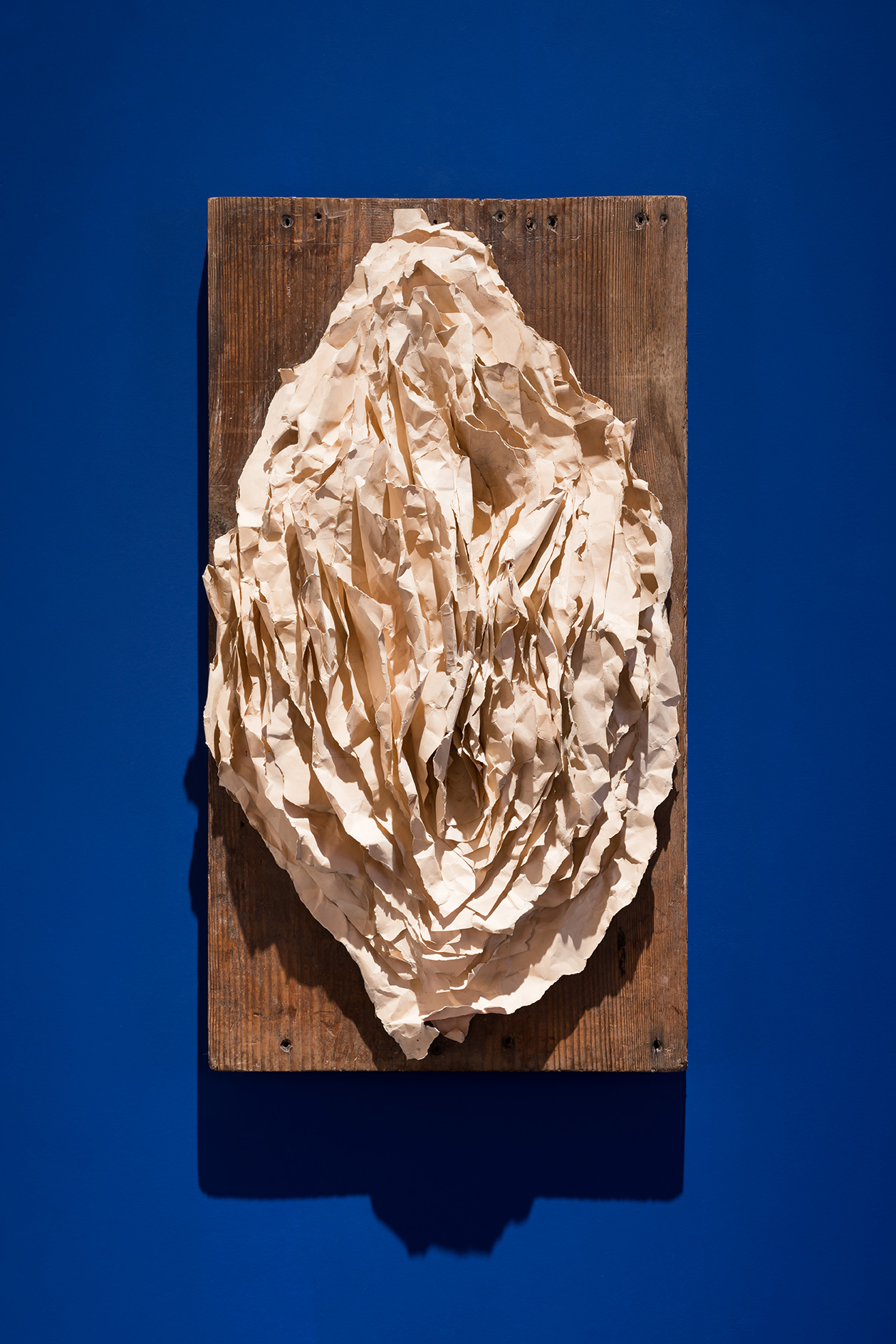

At the end of the corridor, we were faced with a work that could not be more different in its delicacy, abstractness, and fragility. List (Leaf) is a late work by Eva Kmentová, a sculptor who left an indelible mark on the history of Czech modern art. And yet, the 1975 piece List is, in a sense, a similar show of directness in expressing one’s own corporeality. The technique corresponds to the artist’s medical condition, which forced her to gradually replace heavy sculptural materials with supple paper. It is both a poetic and entirely clear depiction of a woman’s crotch.

The color of Kmentová’s List brings us to another author, close to Kmentová in more than just being close to her age – the Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow. Her masterpieces from the 1960s and ‘70s are characterized by their great sensuality in depicting (multiplied) fragments of female bodies, including direct imprints (particularly of lips and breasts). At Wells of Wisdom, however, we presented one of Szapocznikow’s oldest surviving works, made while she was a student at the Academy of Art, Architecture and Design in Prague in the studio of Josef Wagner. Szapocznikow was only twenty at the time, making this, in a way, the exhibited work made by the youngest artist. In addition to the directness of this small statuette, we were also captivated by the background narrative, whose mention is, in a sense, an example of Irit Rogoff’s provocative theory on the importance of gossip for the reconstruction of the oeuvres of women artists.6 Irit Rogoff, Gossip as Testimony: A Postmodern Signature, 1996. Szapocznikow allegedly dedicated this statue of a lying nude (with easily identifiable elements of a self-portrait) to her classmate Olbram Zoubek (who later became Eva Kmentová’s husband), whom she was supposedly trying to seduce. In mentioning this personal aspect of the work we are not interested in the “risqué anecdote” as such, but rather the possibilities for interpretation that it offers. In fact, the open, lascivious pose of the lying figure can be read as a confident depiction of one’s own body that is not being claimed by others but is instead offered of one’s own volition and is viewed as a source of one’s own pleasure. As Adriana Primusová quotes, for Szapocznikow, the “human body is the most sensitive and the only source of great joy, all pain, and all truth”. 7Adriana Primusová, Tři sochařky (Three Women Sculptors), catalog of the exhibition at Queen Anne’s Summer Palace in Prague, 2008.

The other works in the rooms running alongside the central corridor are also connected by the motif of looking and relationality; the co-being of bodies. The organic “portals” of Marianne Vlaschits’s oval paintings open up to us, while the female figure in another painting of hers showers us with an abundance of flower blossoms that evoke female corporeality. This is a representation of a fictional religious leader from the science fiction novels Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998) by the African-American writer Octavia E. Butler. In this narrative, Lauren Olamina’s superpower – and burden – is her hyper-empathy with others.

Also telling are the two statues by Eva Kmentová. The archetypally reduced figure has a deep wound in their back. What is it that this Žena, která mlčí (The Woman Who Is Silent) does not wish to say out loud? On the stele, whose scale suggests a human figure, the imprint of the artist’s lips, multiplied, assumes the position of other body parts: in its totality, corporeality is present in a mere fragment whose ambiguity is reflected and reinforced in Marie Lukáčová’s drawings on the floor of the room.

“My experience mostly stems from pain, as women are taught to live with pain. We are all born from pain and usually we die in it. Many transcendent experiences come from pain, which will enrich us in the end. Acceptance is the choice of how to understand and unblock a fear.” – R.D.

In her new installation, Romana Drdová presented three female figures with mysterious names (Vicky, Sanandra, and Utsava) who have recently influenced and inspired her and represent different approaches to the body – the struggle with male energy and one’s own gender ambivalence, the generative power and harmony of one’s own sexuality in relation to magic.

In a short film by the Los Angeles–based artist Zackary Drucker, we follow an intergenerational dialogue between two women focused on the body and relationships. The conversation between mother and daughter, interspersed with humor and allusions, is inspiring in its “banality”, its quotidian atmosphere and commonality, which is often denied to trans people in our cis-normative society, replaced instead by the exoticizing narrative of “otherness”.

The following two rooms were, to a large extent, opposites in their emotional effects. The pink room, with works by Kris Lemsalu, Veronika Šrek Bromová and Jana Želibská, represented a monumental fireworks display, showing the body in relation to spirituality and nature. Upon closer inspection, however, ambivalent elements appeared. Are the hands gripping a gigantic ceramic vagina by Kris Lemsalu’s those of protectors or creeping usurpers? Bromová’s drawings include not only the pleasure of the body but also the pain of unfulfilled desire for what a (specific) body cannot provide or what it must bear. And Jana Želibská’s Triptych, with its reference to sacred classical forms, brings us back, after a few minutes of observation, to Yishay Garbasz’s photographic series, Becoming. The three figures in the paintings turn out to be of ambiguous gender (which, similarly to Yishay’s photographs, is also not affected by their haircuts). With regard to the religious context, we could – from today’s perspective – relate this work, now over fifty years old, to various non-European traditions (India, Siberia, the indigenous people of North America, etc.) in which non-binary and gender non-conforming individuals played – and often still play – important roles as spiritual leaders or mediums.

“A strange bodily sensation when my breasts started growing. Under your skin, you feel a little ball, something will grow out of it, the breast grows larger… you’re almost flat, but the little pellet is there… a period in which me and two other friends examined each other through touch. The hormonal body wakes up and you’re left alone to deal with it, you have girlfriends, that’s good, you share it with them. The pellet is wrapped in tissue, it gets bigger, it grows and grows and grows… your skin chaps. Your first period, on your uncle’s latrine in South Bohemia. You feel weird, you don’t understand, as if you were opening up from the inside into a bottomless pit full of strange pains, there is sticky blood on your thighs, there’s a strange raw scent, you have an inkling of what it is, but it’s still a surprise, you feel caught off guard – thank God your aunt is there.

When you’re thirteen and you’re running to catch a tram and you have D-size bra, there’s no way of explaining what you feel. Or the fact that those around you see you as a sex object and you see that they don’t actually see you, who you are, or what you’re like… and no one cares what you feel and how you feel… All the PMS symptoms you experience throughout your life – that’s not something that can be “rationally” described and understood, though it would make for an interesting book, from the bodies and souls of women.” – V.B.

The last part of the exhibition was intentionally cold; the body is, to a large extent, exposed to violence, presented as vulnerable and mortal. The images by Spanish artist Esther Ferrer are a clear reminder that a woman’s bosom is a particularly sensitive and threatened part of the body. Jana Želibská’s Pudding for Two pursues this even further, reminding us of the importance of breasts for our species whilst also showing them without embellishment as a product to be consumed. With this, she also alerts us to the reality that women are often reduced to this dimension, with the care they provide (not only) to their offspring trivialized as a biological necessity instead of society truly valuing it in depth, both symbolically and practically. The title of the ceramic torso by the Belgian artist Aline Bouvy, Primitive Accumulation, also calls attention to the economization of bodies; their labor and “use”. A series of photographs by Anna Daučíková, Výchova dotykom (Education by Touch) presents a clear glass pane that acts as an invisible barrier and shield. The body pressed against this transparent plane can be viewed both as an erotic object as well as a subject that is actively defying the definiteness of its body by transforming it. 8We may think of the breast/chest binding done by some trans and non-binary people, partly in an attempt to alleviate or deal with gender dysphoria, i.e., a stress state arising from the discrepancy between an individual’s gender identity and the gender ascribed to them by their surroundings. And, finally, Julie Béna’s film is a dense and many-layered statement on the experiences of (one’s own) body, which can be painful and traumatizing as well as cathartic and emancipatory.

As film theorist Vivian Sobchack summarizes in her epilogue to Yishay Garbasz’s book Becoming: “We don’t just ‘have’ a body. We ‘are’ our bodies. They come and become (with) us as we grow and age. Our familiars, they provide us continuity, the place upon which experience gathers and inscribes our adventures in the world and with others. Our bodies enable and accompany us—marked by and marking our on-going journey through our lives. Nonetheless, however familiar, our bodies are always also strange in their ongoing indifference to staying the same.” (Vivian Sobchack, “On Becoming”, in Yishay Garbasz: Becoming, 2010, p. 186)

“As a white straight woman, I had to defend my body, to claim it back, but I never felt other from it, except in a few extreme and specific situations. Who am I to speak about otherness? All your gaze, experiences, situations, points of view, are linked to what you are and what you lived, so if I am not Tiresias, I won’t even be able to tell you, what I gained or not, because anyway my situation, my body, remained what it is until now.” – J.B.

Curators Tereza Jindrová and Eva B. Riebová spoke with the artist Julie Béna, whose work is part of Wells of Wisdomexhibition, and the artist Ezra Šimek, Béna´s former student and one of current laureates of the Chalupecky Award 2022, about the relation between their work and their body, what they learnt about themselves and the society thanks to their bodies, the construct the binary gender, and about hope that can be found amongst today´s kids for whom a pregnant men can be an ordinary thing.

Concept: Tereza Jindrová

Line up:

Mary Maggic: Genital(*)Panic, 2021

Tabita Rezaire: Sugar Walls Teardom, 2016

Ezra Šimek: Do They/Thems Like Flowers or Do I Buy Platform Shoes and Tarot Cards?, 2021

Helena Aleksandrova: We Are Lady Godiva They Are Peeping Tom, 2019

The accompanying screening of the exhibition Wells of Wisdom presents videos / short films that

follow the concept of the exhibition and further expand it. The main motive of the selection is non‑normativity – exposing and rejecting restrictive norms that prevail in patriarchal society.

Video manifesto Genital (*) Panic by Mary Maggic draws attention to the changes in our bodies, specifically the genitals, which are associated with increasing toxicity in the environment. At the same time, it presents a vision of a bottom‑ up database of „alien bodies“, which can be a tool for questioning dominant scientific classifications that are discriminatory and pathologizing to differences.

The video Sugar Walls Teardom by Tabita Rezaire obscures the key role played by the womb of Black womxn in advancing modern medical science and technology. As part of slavery, their bodies were used and abused as commodities – for hard work on plantations, sexual slavery, reproductive exploitation and medical experiments. Anarcha, Betsey and Lucy were among the captive „guinea pigs“ of Dr. James Marion Sims, the so‑called „father of modern gynecology,“ who tortured countless enslaved womxn in the name of science.

In their video, Ezra Šimek focuses on the phenomenon of so‑called gender euphoria and dysphoria, which is often experienced by trans and non‑binary people. Gender dysphoria is a feeling of anxiety caused by the desire to have the physical characteristics of the sex with whom you identify, but which were not assigned to you at birth. Gender euphoria, on the other hand, is the feeling of joy that such a person can have when living his or her true gender identity. At the same time, dysphoria and euphoria are inextricably linked to how a person is (not) received by their surroundings. In the video, Ezra Šimek presents a very personal statement, which at the same time has a largely manifestational (and educational) character and thus addresses, among other things, all those who identify as allies of gender non‑conforming persons and queer communities.

Helena Aleksandrova’s short film We Are Lady Godiva They Are Peeping Tom explores how we see a woman’s body and body hair in real life and in an online environment. It is a reflection on the standards of beauty, voyeurism and sexualization. She brings these topics together through the story of Lady Godiva, whose hair served as a protection of chastity, and Peeping Tom, who was punished for looking at her with an intensity that we unfortunately rarely encounter in sexual assailants in reality. In the film, the artist interviews several women (including her mother) about the perception of beauty and her own body in connection with social expectations.

The selection of screened films thus underlines the diversity (of our bodies and identities) as one of the key sources of wisdom that is so often left behind.

Wisdom — or here, I am actually going to refer to it as “Other Wisdom”… It is the inherited wisdom. It is the wisdom that was squirreled away in corners. And in spaces not meant for it to exist. Because we have our wisdom, we have our University PhDs, we have… all this wisdom.

And yet this wisdom is also pale. Male and white. This wisdom is a privilege, which is another way of saying, leaving out… leaving out the margins, leaving out “lower wisdom”. Unrefined wisdom, dirty wisdom. And yet this wisdom still exists.

Trans, queer, working-class, immigrant. The dirtiest of wisdom that yet supported life, that yet supported survival, that yet nourishes those of us that were not meant to survive. Those of us that were not meant to exist.

This wisdom, this Other Wisdom that we carry in our bodies, that we carry in our hearts. They came to us from our ancestors. Through the lineages of mothers, through the lineages of the non-binary.

It was inherently a wisdom that was kept in the dark. Hidden. And exists in spaces it was not meant to, which is mirroring our existence because we were not meant to. With all the laws that are now coming against bodily autonomy, against the Other, valorising some kind of white supremacist family ideal.

And, you know, we still exist. And we still have a knowledge that is sought after, that is constantly stolen and appropriated by those in power. But through that appropriation, it became pale again. Lacking meaning. Anaemic. Because knowledge and we are not separate. The knowledge and queerness are not separate. Knowledge and migration are not separate. Knowledge and our bodies are not two things.

It is also the knowledge of my Jewishness. The Jewish people were not meant to exist. We’re particularly hunted and forbidden from existing and yet the knowledge still comes down through the generations. And today, more than ever, we need that knowledge.

Because those with addiction to power, those whose addiction to hoarding resources — to multi-generational hoarding of resources — are driving us directly off the cliff. And if we want to survive, this is something that has to happen together. And we have to bring the knowledge from the margins and center it, which means we have to bring people from the margins and center them. Listen to their leadership.

Because if we don’t do that, we’re letting go of our best chance because those marginal knowledge are the ones carried forward in the bodies of people that were not meant to survive and yet still survived.

And that is knowledge from more than one person, because each of us that survives, that endures yet another day, is an accumulation of all our ancestors. And that is not a limited biology. Queer lineages and queer knowledge transmit themselves in between the words, in between the spaces.

Which is the same as trans knowledge, which is the same as Jewish knowledge. And they all come together in this one body, in my body and other bodies. That we’re not meant to exist. And while PhDs are amazingly powerful tools, lived experience, the day-to-day assault on life and dignity, the living in the margins is… Those of us that are still alive have that knowledge, that Other Knowledge, that medical knowledge. It transforms. It centres on love. It centres the community. It centers ways other than those who can know.

And other, especially other than knowledge that we were taught in school. It’s a possibility. Obvious things that aren’t known. Which all the systems we exist in today are opposed to, are fighting against that unknown. But that unknown is change, that unknown is surviving through the cracks, and that’s what we must embrace if we want to still be alive. In a pandemic, while the world is burning and most of the world doesn’t own as much as 0.1% of the world does when a billionaire can ride a rocket penis into space because he feels like it and create the same pollution as 2 billion people will in their whole lifetime.

There is medicine for this. But it’s not in any giant pharmaceutical company. It is medicine for all of this but it is in the hands of those that are too dirty to be counted. Living in the corners and the cracks. And without centring, without seeing, without honoring and appreciating, we will not have access to that knowledge. And that knowledge is not necessarily transmitted via logic. It is a special knowledge that goes around the words, inside the words, in the cracks between the words that can help set us free.

And it is a knowledge of us because it is bigger than one body and it is the liberation of all bodies. With the type of bodies yet unknown. It is the medicine that will heal us. It’s a medicine made by all the unwanted bits that each of us had to throw away in order to fit in.

It is those bits, those exact bits that didn’t allow us to fit in, that have the most knowledge to give us, that possess this medicine. And those whose lived experience is of being battered daily, of being assaulted daily, of being invisible daily, have the biggest treasure of knowledge, of Other Knowledges.

I want to say, looking forward is critical but so is looking back. Leaving no one behind because the ones left behind are the missing keys for a future.